The ‘New Age’ of which Fritjof Capra has become a celebrated spokesperson, and Antonio Gramsci’s ‘Cultural Revolution’ have something in common: both aim to introduce vast, profound, and irreversible changes in the human spirit. Both call for a break with the past and propose a new heaven and a new earth to humanity. The former has been making immense repercussions in Brazilian scientific and business circles. The latter, without making as much noise, has been exerting a significant influence on the course of political and cultural life in this country for three decades. Neither of the two has ever been subjected to the briefest critical examination. Accepted out of mere first-sight sympathy, they penetrate, propagate, gain power over consciousness, and become decisive forces in the lives of millions of people who have never heard of them, but suffer the effects of their cultural impact. For the conscious adherents and propagators of these two new proposals, nothing is more comforting than the astounded passivity with which the literate Brazilian public receives, admits, absorbs, and copies everything, with that talent for mechanical imitation that compensates for the lack of true intelligence.

- Epigraph

- General Introduction to the Trilogy

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Prefatory Note [from the 1st edition]

- I – Lana Caprina, or: The Wisdom of Mr. Capra

- II – St. Antonio Gramsci and the Salvation of Brazil

- III – The New Age and the Cultural Revolution

- Final Remarks

- Appendices

- The Left and Organized Crime

- The PT’s Brazil

- Bandits and Scholars

- Gramscian Mafia

- Effects of the “Great March”

- Measuring Words

- Trying to See

- An Enemy of the People

- Diffuse Indoctrination

- The Gurus of Crime

- Cultural Marxism

- Revolutionary Transition

- Antonio Gramsci and the Theory of the Scapegoat

- What Is Hegemony?

- Our Media and Its Guru

- Double Blindness

- Invisible Dominator

- The Clarity of the Process

- Fattening the Pig

- Cooking the Frog

- The Masters' Recipe

- The Unity of Duplicity

- Calling Things by Their Name

- The Outsourced Gestapo

- Why Brazilians Vote for the Left

- From Depressing Fantasy to Fearsome Reality

- Losing the Culture War

- Rounding the Squares

- Social Revolution

- Useless Memories

- The Camouflage of Camouflage

- Afterword: A Conversation with the Author Two Decades Later, by Silvio Grimaldo

- Credits

Epigraph

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS,

The Second Coming

General Introduction to the Trilogy

User Manual of The Collective Imbecile: Brazilian Incultural Current Affairs and the preceding volumes: The New Age and the Cultural Revolution: Fritjof Capra & Antonio Gramsci and The Garden of Afflictions: From Epicurus to the Resurrection of Caesar – Essay on Materialism and Civil Religion.1

THE COLLECTIVE IMBECILE concludes the trilogy that began with The New Age and the Cultural Revolution (1994) and continued with The Garden of Afflictions (1995).

Each of the three books can be understood independently of the others. What cannot be done is to grasp the essence of thought that guides the entire trilogy through only one of them.

The purpose of The Collective Imbecile in the collection is quite explicit and was stated in the preface: to describe, through examples, the extent and seriousness of a state of affairs – current and Brazilian – which The New Age had alerted to and whose precise location in the overall evolution of ideas in the world had been diagnosed in The Garden of Afflictions.

Therefore, the meaning of the series is clearly to situate contemporary Brazilian culture within the broader framework of the history of ideas in the West, in a period that goes from Epicurus to Chaim Perelman’s “new rhetoric.” To my knowledge, no one has made an effort to think about Brazil on this scale before. My only predecessors seem to have been Darcy Ribeiro, Mário Vieira de Mello, and Gilberto Freyre, the first with his tetralogy starting with The Civilizing Process, the second with Development and Culture, and the third with his entire work. However, I differ from them in essential differences: Ribeiro employs a much larger scale, starting with Neanderthal Man, but at the same time, he seeks to encompass this immense territory from the perspective of a particular empirical science, Anthropology, based on a disappointingly narrow philosophical foundation, which is naked and crude Marxism. Vieira de Mello, with much greater philosophical breadth, does not venture back beyond the period of the French Revolution, with a few incursions into the Renaissance and the Reformation. As for Gilberto, the cycle that interests him is the one that begins with the great navigations. In general, scholars of the Brazilian identity have assumed that since Brazil entered History in the so-called “modern” period, there was no need for Brazil to try to see itself in a broader temporal mirror. Therefore, I am alone in the game, and I can claim in my favor the formidable merit of originality.

Formidable because originality is singularity, and the human mind is ill-equipped to perceive singularities as such: either it immediately expels them from the circle of attention to avoid the discomfort of adapting to an unknown form, or it apprehends them only through partial and superficial analogies that incorrectly assimilate them to some class of known objects. Between silent rejection and loquacious deception, my trilogy does not have many chances of being well understood.

But singularity, in it, is not only in the subject matter. It is also in the philosophical postulates that underlie it and in the literary form that I chose to present it, or rather, that was imposed on me by the nature of the subject matter and the circumstances of the moment.

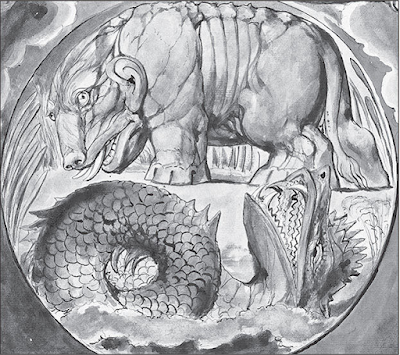

Regarding the form, the reader will notice that it differs in the three volumes. The first one consists of two medium-sized essays, placed between two introductions, several appendices, a handful of footnotes, and a conclusion. At first glance, the whole gives the idea of texts of diverse origins brought together by the fortuitous coincidence of subject matter. Upon closer examination, it reveals the unity of the underlying idea, embodied in the symbol that I had printed on the cover: the biblical monsters Behemoth and Leviathan in William Blake’s engraving, the former heavily ruling over the world, the massive power of its belly firmly supported by four legs, the latter writhing in the depths of the waters, defeated and fearsome in its impotent rancor.

I used Blake’s engraving not for its beauty but to indicate that I attribute to these symbols exactly the meaning that Blake attributed to them. This is an important detail because this interpretation is not a poetic allegory, but, as Kathleen Raine noted in Blake and Tradition, the rigorous application of the principles of Christian symbolism. In the Bible, God shows Behemoth to Job, saying, “Behold Behemoth, which I made with thee” (Job 40:10). Taking advantage of the ambiguity of the Hebrew original, Blake translates “with thee” as “from thee,” indicating the unity of essence between man and monster: Behemoth is at once a macrocosmic power and a latent force in the human soul. As for Leviathan, God asks, “Canst thou draw out leviathan with an hook? or his tongue with a cord which thou lettest down?” (Job 40:21), making it clear that the force of rebellion lies in the tongue, while Behemoth’s power, as stated in Job 40:11, lies in the belly. There could not be greater clarity in the contrast between psychic power and material power: Behemoth is the massive weight of natural necessity, Leviathan is the diabolical infranature, invisible under the waters – the psychic world – that it agitates with its tongue.

The meaning that Blake records in these figures is not an “interpretation” in the negative sense that Susan Sontag gives to this word: it is, as should be all good readings of sacred texts, the direct translation of universal symbolism. For Blake, although Behemoth represents the set of forces obedient to God, and Leviathan the spirit of negation and rebellion, both are equally monsters, cosmic forces disproportionately superior to man, who fight against each other on the stage of the world, but also within the human soul. However, it is not up to man, nor to Behemoth, to subjugate Leviathan. Only God Himself can do it. Christian iconography shows Jesus as the fisherman who pulls Leviathan out of the waters, tying its tongue with a hook. However, when man shies away from the inner struggle, renouncing the help of Christ, the destructive struggle between nature and the rebellious antinatural or infranatural forces is unleashed, transferring from the spiritual and inner sphere to the external stage of History. This is how Blake’s engraving, inspired by the biblical narrative, suggests with the synthetic force of its symbolism a metaphysical interpretation of the origin of wars, revolutions, and catastrophes: they reflect man’s resignation in the face of the call of inner life. By shying away from the spiritual struggle that frightens him but that he could overcome with the help of Jesus Christ, man exposes himself to dangers of a material order in the bloody scenario of History. In doing so, he moves from the realm of Providence and Grace to the realm of fate and destiny, where the appeal to divine help can no longer have an effect because there, the truth and the error, the right and the wrong, are no longer confronted, but only the blind forces of relentless necessity and impotent rebellion. In the context of more recent History, that is, in the cycle that begins more or less at the time of the Enlightenment, these two forces clearly assume the meaning of rigid conservatism and revolutionary hubris. Or, even more simply, right and left.

The entire drama described can be iconographically summarized in the cross diagram that I placed afterwards in The Garden of Afflictions, but which is already implied in The New Age and the Cultural Revolution, as it constitutes the very structure of the analytical approach by which I seek to grasp the significance of the two currents of thought mentioned in the title: Fritjof Capra’s neocapitalist holism and Antonio Gramsci’s cultural devastation enterprise.

In this first volume, the initially adopted form could not be clearer and was imposed by the very nature of the subject matter: an introduction, one chapter for Capra, another for Gramsci, a comparative retrospective, and an inescapable conclusion: ideologies, whatever they may be, were always limited to the horizontal dimension of time and space, opposing the collective to the collective, the number to the number; lost was the vertical dimension that linked the individual soul to the universality of the divine spirit, the singular to the Singular. Along with it, the sense of scale, the sense of proportions and priorities, was lost as well, so ideologies tended to totally occupy the entire stage of spiritual life and simultaneously deny metaphysical totality and the unity of the human individual, reinterpreting and flattening everything into the mold of a one-dimensional worldview.

The footnotes and appendices, which apparently bring some disorder to the form of the whole, serve two opposite and complementary purposes: on one hand, they indicate the broader foundations that the argument kept implicit, showing the reader that Capra and Gramsci’s analysis was just the visible tip of a much broader investigation that, at that time, only my students knew through the lectures and handouts of the Philosophy Seminar, but which, under the conditions of an abnormally busy life, I was not sure I would ever be able to write in full; on the other hand, they indicate that my analyses do not hover in the realm of mere theories, but that they apply to the understanding of political facts unfolding in the Brazilian scene at the very moment I was writing the book – hence the polemical edges that give certain passages of this essay the appearance of combat journalism. If some readers saw in the book no more than this surface – just as others will see in The Collective Imbecile only a timely critique of certain public figures of the day and in The Garden of Afflictions an attack on the USP establishment – I cannot say that they have missed anything because the rest and the best of what these books contain were not really made for those readers, and it is good that it remains invisible to their eyes.

If in the first volume I allowed the central idea to be only outlined in fragments, somewhat minimalist in style, so that the reader, rather sensing it than perceiving it, had the task of seeking it from the depths of himself instead of simply taking it from the surface of the page, in the second volume, The Garden of Afflictions, I followed the opposite strategy: to be as explicit as possible and give the exposition the maximum unity, forcing the reader to follow a dense argumentation, without leaps or interruptions, over four hundred pages. But in order not to give the illusion that this complete form encompassed the totality of my thinking on the subject, I scattered throughout the text hundreds of footnotes that indicated the implicit theoretical assumptions, the possibilities for further exploration (already accomplished orally in lectures or yet to be done), and a thousand and one seeds of possible and interesting developments that I would accomplish if I had an endless life, but which intelligent readers can well accomplish on their own. The unity of argumentation in The Garden of Afflictions, which in my intention, confirmed by some readers, gives this otherwise extremely heavy and complex book the readability of a detective novel, thus shows that it is not the closed unity of a system, but the unity of a holon, as Arthur Koestler would say: something that, seen from one side, is a whole in itself, and from the other side, is part of a larger whole. This homology of part and whole is, in turn, repeated in the internal structure of the book, where the apparently insignificant event that serves as its starting point already contains, in its microcosmic or microscopic scale, the general lines of the global interpretation of the history of the West, which is presented in the remaining chapters. Those readers who complained that such a substantial book began with the polemical comment on a minor event did not understand well one of the main messages of the book, which is that, in light of a metaphysics of History, there are no properly insignificant events – the great and the small are cohered in the organic unity of a Meaning that pervades everything. What weighs nothing in the causal order can reveal much in the order of significance.

And, indeed, if there were perfectly insignificant events that deserved nothing but contempt and silence, the third volume of the series, The Collective Imbecile, could not even have been written: because what I present there is a commented showcase of cultural banalities that carry much significance precisely because they are worth nothing. And if I decided to gather them in a volume, giving them the dignity of being remembered when their authors are nothing more than shadows in Hades, which is the grave of the irrelevant, it was precisely because I understood that, starting from each of them, and turning in ever-widening concentric circles, one could arrive at visions of universal scale similar to the one in which, starting from a cultural squabble that occurred at the São Paulo Art Museum in 1990, I showed the readers of The Garden of Afflictions the combat of Leviathan and Behemoth on the entire horizon of Western history. And since I cannot undertake such a hermeneutic effort with every new cultural idiocy I read in the newspapers, I decided to gather some of them and offer them to readers as samples for the purpose of exercise. The Collective Imbecile is, therefore, the book of tasks that accompanies the basic text brought in The Garden of Afflictions, with The New Age as an abbreviation for beginners. Whoever reads The Collective Imbecile in this way, seeking there the homework to reconstruct, from thirty examples, the outlines of the vision of History and the interpretive method exposed in the previous volumes, and always seeking the organic unity between the part and the whole, between the philosophical vision of a millenary culture and the samples of the momentary inculture of a country forgotten on the fringes of History, will have won for himself the best part of what I have given him. For that is how one reads the books of philosophers, even when it is only a little philosopher like this one who is speaking to you.

I admit that if I had adopted a more academically favored expository form in any of the three books, I would not need to draw attention now to a unity of thought that would be apparent at first glance. But this visibility would come at the cost of losing all references to authentic life and the imprisonment of my discourse in a linguistic bubble that does not match either my temperament or the rule that I imposed on myself some years ago of never speaking impersonally or in the name of some collective entity, but always directly in my own name alone, with no more respectable backing than the mere honorability of a rational animal, as well as never addressing abstract collectivities, but always and only addressing individuals made of flesh and blood, stripped of the temporary identities that office, social position, and ideological affiliation superimpose upon the one they were born with and with which they shall appear one day before the Throne of the Most High. I am deeply persuaded that only at this level of discourse can one philosophize authentically.

Furthermore, there is some pedagogical merit in not being too tidy, in being able to present the data not in the most customary order that a lazy viewer would desire, but intelligently disarranging them in a way that forces the reader to actively participate in the investigation. And there is immense pleasure in mixing literary genres when one is the author of a booklet that previously distinguished and cataloged them with refined formal rigor.2

I am immensely pleased to have been able to complete this trilogy and to be here today, in this celebration that, to me, is less about the book launch and more about the conclusion of a part, of a stage of the task that falls upon me in this life. The task, essentially, is to break the circle of limitations and constraints that ideological discourse has imposed on the intellect of this country, to connect our culture to the ancient and higher currents of spiritual life in the world, and, in short, to make Brazil, instead of only looking at itself in the narrow mirror of modernity, imagining that four centuries constitute the entire history of the world, be able to see itself on the scale of the human drama in relation to the universe and eternity. The task, in its highest and most ambitious intention, is to remove the mental obstacles that currently prevent Brazilian culture from receiving a stronger inspiration from the divine spirit and from flourishing as a magnificent gift to all of humanity.

Preface to the Second Edition

After a few months from the first edition, which quickly sold out, events have only served to rapidly confirm the diagnoses I presented in this book.

On one hand, Brazil is experiencing a profound crisis of intelligence, reflected in the foolish enchantment with which we receive and exalt the most senseless and absurd ideas that come to us from abroad, considering them as high intellectual achievements. Mr. Capra was not the last in this series. After him, we welcomed the visit and insights of Mr. Richard Rorty, whose proposal, philosophically indecent and morally repugnant, local thinkers dared to criticize only with precautions and apologies that bordered on servility.3

This phenomenon is, in part, a passive effect of the crisis of American intelligence, as I explain in another book that will be published soon after this second edition.4

However, on the other hand, it is also the result of a deliberate policy pursued by leftist movements interested in reducing all Brazilian intellectual life to a unanimous chorus of complaints. The debasement of the arts, philosophy, and even some sciences to the condition of megaphones for revolutionary propaganda, a temptation that the best Marxist thinkers always rejected as demeaning, has become the established practice that no one dares to question. This is less due to fear of explicit retaliation than to the absolute certainty that the listeners are now incapable of understanding, so far are they from imagining that culture can have other and higher purposes. The dogma of militant culture was not adopted as a conscious option, victorious in a confrontation with other possible conceptions; it stealthily infiltrated, as an implicit assumption, taking advantage of the ignorance of the new generations, who, upon awakening to the world of “culture,” already find it identified with ideological propaganda as if this were its natural state and eternal destiny. What is worse is that this propaganda no longer even conveys ideas or symbols of a revolutionary doctrine; it merely repeats, in a shallow, literal, and direct manner, the demands of the day: down with Collor, death to the corrupt, long live Betinho, we want sex. All the dwarfs in Congress, united and combined, have not caused as much harm to this country as this complete prostitution of intelligence to immediate political ambitions and the most commonplace passions. Lost money can be regained; when the spirit departs, it does not return. Abandoned temples, as universal experience shows, become forever dens of sorcerers and bandits.

Due to the combined effect of American decline and local action aimed at molding and merging all the minds in this country into the faceless mold of the Gramscian “collective intellectual,” the fact is that national intelligence is spiraling downward while a somber rumbling of revolution is rising from the streets and fields.

Yes, Brazil is unequivocally entering an atmosphere of communist revolution. Imbecilization is just a symptom: the temporary obscuring of light mentioned by the I Ching, in which, among the folds of the night, monsters are generated that will populate the visions of a fearsome awakening.

These monsters are no longer so small that a discerning eye cannot see them and be astonished at how quickly they are growing in the womb of national unawareness.

The very unanimity of the intellectual elite is one of the signs. But another seemingly contradictory sign is the proliferation of guild demands, the spirit of division, at a time when the country most needs the sacrifice of its parts for the good of the whole. In every class, in every region, in every union, in every company, in every family, in every soul, one notices an acute and exasperated sense of one’s own rights and a complete dulling of the sense of duty. It is the disastrous predominance of demanding and protesting over creating and offering. The less one fulfills their obligation, the more they believe they have the right to accuse others. The government represses excessive price increases while protecting high interest rates and fueling the gigantic petroleum tapeworm, which, through periodic fuel price hikes, sets the pace for the generalized rise in the cost of living. The head of the household rants against political corruption while asking an accountant to “touch up” their income declaration to make the lie more plausible and exempt them from taxes. Companies censure the government while raising the prices of their products and services above what the law allows and decency recommends. The left cries out against the oligarchies while organizing strikes by public employees directly aimed at the rights of the population. Intellectuals and artists decry injustices while living like princes at the expense of public funds. The press accuses, denounces, and exposes individuals and institutions to infamy while discreetly, in professional congresses away from the public eye, confessing its own lack of decorum, ethics, and dignity. Landless workers display their touching poverty before the cameras while spending fortunes on paramilitary operations that the army itself would not have the budget to sustain. The discourse of unanimity, like the enthusiastic chorus of fans during the World Cup, is nothing but a substitute, the ostentation of a feigned unity that conceals the cowardly and ruleless struggle of all against all. Selfishness, unawareness, and malice gain ground with each new onslaught of the “Campaign for Ethics.”

Quia bono? Who benefits from the crime? Who profits from the tearing apart of the national soul in a vile confrontation of all selfishness and unawareness? Opinion polls respond that, of all Brazilians, the only one who is not afraid of being happy has already gained forty percent of the intentions to vote for the Presidency.

This could be a coincidence, an accidental effect of circumstances. However, if we step back and search for its roots, we see that this effect has long been desired and meticulously prepared by the most skillful and talented generation of activist intellectuals ever born in this country. It is the generation that, defeated by the military dictatorship, abandoned the dreams of attaining power through armed struggle and silently dedicated itself to a revision of its strategy in light of the teachings of Antonio Gramsci. What Gramsci taught them was to renounce overt radicalism in order to broaden the margin of alliances; to relinquish the purity of apparent ideological schemes in order to gain efficiency in the art of enticing and compromising; to withdraw from direct political combat and delve into the deepest zone of psychological sabotage. With Gramsci, they learned that a revolution of the mind must precede the political revolution; that it is more important to undermine the moral and cultural foundations of the adversary than to win votes; that an unconscious collaborator, whose actions the party can never be held responsible for, is worth more than a thousand registered militants. With Gramsci, they learned a strategy so vast in its scope, so subtle in its means, so complex and almost contradictory in its simultaneous plurality of channels of action, that it is practically impossible for the opponent not to end up collaborating with it in some way, unwittingly weaving the rope with which they will be hanged, as Lenin prophesied.

The formal or informal, conscious or unconscious conversion of the left-wing intelligentsia to Antonio Gramsci’s strategy is the most relevant fact in the national history of the last thirty years. It is in this conversion, as well as in other concurring and converging factors, that one must seek the origin of the far-reaching psychological mutations that are pushing Brazil into a clearly pre-revolutionary situation, which until now only two observers, besides the author of this book, have known how to indicate, and moreover very discreetly.5

The expectation, hope, and longing for revolution are so old, so deeply rooted in the soul of the national intelligentsia6 that, even in the face of the worldwide failure of socialism, it will not have the strength to resist the temptation to carry it out now that the local situation, for the first time in our history, offers the means to seize power. Brazil indeed has a chronic mismatch with the time of universal history. The global recognition of the debacle of communism resonated in this country—paradoxically, according to human logic, but consistently, according to the constant line of national history—as a touch of hope: our turn has come to achieve what no one else wants anymore.

For some time, I nurtured the senseless hope that the Workers' Party (PT) would expel the Gramscian poison from itself and become the great socialist or labor party that Brazil needs to counterbalance the seemingly irreversible neoliberal advance in the world. By the healthy play of forces, it could provide the regular and harmonious movement of power rotation that is the normal pulse of a democratic organism. Driven by this illusion, I voted for Lula as president. Today, I wouldn’t vote for him even as a city councilor in São Bernardo. It’s because, through the succession of events since the impeachment campaign, the PT has shown its surprising vocation to me as a manipulative and coup-minded party capable of leading the country down the fraudulent paths of Gramscian “passive revolution.” It employs the most cowardly and illicit means—political espionage, psychological blackmail, the prostitution of culture, the sabotage of corrective measures, hysterical agitation that appeals to the lowest sentiments of the population—and adorns this package of filth with a moralistic discourse that reeks of the sacristy. The party that, to sabotage a candidate, promotes something like a “preventive strike” during the launch of a new currency under the astonishing claim of a “theoretical possibility” of future wage losses, knowing that this strike will result in an increase in fuel prices and a resurgence of inflationary cycles, factitiously confirms retroactively the announced damages. Frankly, it has decided to imitate the devil: it produces evil in order to generate hatred within it and accusation speeches from that hatred. The strike of the oil workers failed, but it is the purest example of what the people call “an appeal”: an extreme recourse used for frivolous purposes.

If the PT does this, it is because it has lost confidence in the majestic future to which our developing democracy destined it. Excited by signs of a momentary success that it fears will never be repeated, it has decided to bet everything on the voracious and suicidal game of “it’s now or never.” It no longer wants only to elect the president, govern well, subject its performance to the popular judgment in five years, and make history at the slow and natural pace of the mills of the gods. It wants to seize power, make the revolution, dismantle its adversaries, and permanently expel those who could defeat it in future elections. In the words of Murillo Mendes’s poetry, it has chosen “the swift propellers of evil over the slow sandals of good.” The Gramscian mythology, pompously diagnosing the “transition to a new historical bloc,” has given verbal legitimacy to these aspirations, and now Brazil, having barely embarked on the path of democracy, hastens to abandon it for the shortcut of revolution. Where it leads, the world knows, but what does the world’s knowledge matter to the hordes of underage voters whom the leftist flattery, consecrated in constitutional norms, has turned into the decisive portion of the electorate, giving them power before giving them education? What matters is to seize the moment, at any cost, carrying Lulalá on the shoulders of angry, insolent, and illiterate boys, and before the “passive consensus” of the population has time to assess what is happening, irreversibly hitch the country to the car bomb that hurtles downhill toward revolution.

The generation that reached adulthood at the moment when the dictatorship closed the doors of political life is now fifty years old. Throughout the last thirty years, they waited, dreamed, planned, desired, and coveted with tears of impotent rancor, and above all, they read a lot of Antonio Gramsci. The fact that the socialist revolution has already shown its true face to the world, that it has already proven unequivocally that “it’s not worth it,” matters little. The generation of guerrillas will do what it has long prepared to do. It matters little that, according to the world’s clock, the hour has passed. For the garbage collector, the end of the party is the signal that “his” party is about to begin.

For these reasons, this book, seemingly made up of disconnected fragments, is starting to show, through the force of external events, the unity that the author did not have the time or ingenuity to give it on the literary plane. Under the compromising appearance of a historical salad that mixes Lenin, the I Ching, Max Weber, Freud, and the Red Command, it points out, in order and, I believe, logically, the symptom and the cause of the Brazilian intelligentsia’s illness: at least part of the origin of our vulnerability to Mr. Capra’s false message lies in Antonio Gramsci’s ideas, put into practice by the generation of leftist intellectuals who, on Ilha Grande, acted as midwives to the Red Command and who now set the tone of mental life in this country. If in the first edition, I couldn’t provide a continuous and cohesive exposition of this phenomenon, having to adopt instead a prismatic and unbalanced approach, suggesting it in fragments rather than declaring the meaning of the whole explicitly, it was not due to any profound intention; it was due to a genuine inability to do otherwise. But I don’t believe I deserve censure for it. After all, here, in a rough and fragmented manner, I said what no one else said in any way. The first one to outline the unity of a confused picture is not expected to be complete, and the first one to announce a terrible danger is not expected to speak clearly and orderly according to good style. Breathless and stuttering, half-crazy and abstruse, it finally provides an emergency service. As an Arab proverb says, "Do not look at who I am, but receive what I give you."7

Rio de Janeiro, June 1994.

Prefatory Note [from the 1st edition]

The “New Age” of which Fritjof Capra became a celebrated spokesperson and Antonio Gramsci’s “Cultural Revolution” have something in common: both aim to introduce vast, profound, and irreversible changes in the human spirit. Both call for a break with the past and propose to humanity a new heaven and a new earth.

The first has been gaining immense repercussion in Brazilian scientific and business circles. The second, without making as much noise, has been exerting a marked influence on the course of political and cultural life in this country for three decades.

Neither of the two has ever been subjected to the briefest critical examination. Accepted by mere first sight sympathy, they penetrate, spread, gain power over consciences, become decisive forces in the conduct of the lives of millions of people who have never heard of them, but who suffer the effects of their cultural impact.

For the conscious adherents and propagators of the two new proposals, nothing is more comforting than the stunned passivity with which the Brazilian educated public receives, admits, absorbs, and copies everything, with that talent for mechanical imitation that compensates for the lack of true intelligence.

But Gramsci’s Cultural Revolution and the New Age movement are not simple trends that can be adopted and abandoned at will, with the nonchalance of someone changing underwear. They are proposals of immense scope that, once accepted, even implicitly, informally, hypothetically, lead to consequences of incalculable reach. These consequences will certainly not spare those who have adhered to their causes as a mere pastime, without clear consciousness of the responsibilities at stake. They will spare no one within their radius of action. And we all are.

It is therefore a suicidal frivolity to absorb ideas like these without a preliminary critical examination. It is this examination that I inaugurate in this booklet, aware that in doing so, I anticipate a sluggish public opinion that has not yet remotely raised the issues discussed here, but not for this reason do I do it with less delay in relation to the demands of my own conscience, which has demanded this work from me since I first spoke in public on these matters in 1987. A prolific speaker, I am slow to write, which is why my sense of urgency sometimes turns into a feeling of guilt. The urgency, in this case, was to clarify the connection between those two streams of thought; a connection that, once perceived, reveals the inconsistency of both, and frees us from both. By not perceiving it, the Brazilian mind today spins futilely around the axis marked by these two poles. By the number of adherents and the strategic positions that some of these occupy in society, Capra and Gramsci dominate the two most active mental currents in this country. The fact that they have never been confronted and that the very idea of confronting them sounds strange only shows that the country is not clearly aware of the alternatives in which it struggles, and that mental life in it tends to split into separate devotions to gods who do not know each other and who mutually antagonize each other in the dark, like blindfolded swordsmen. It is therefore a question, here, of clarifying a subconscious conflict, in which the fate of a country is decided among the shadows of a dream. Sleepwalking Brazil: why do you support your intellectuals with money and flattery, if not to reveal yourself, to tell you what is going on with you beyond the surface of the news?

The three chapters that make up this book reproduce, as much as possible, the content of classes and lectures I gave on their respective topics, whether in the Permanent Seminar on Philosophy and Humanities, which I direct at the Institute of Liberal Arts,8 or outside of it. The chapter on Fritjof Capra was written and distributed to my students in September 1993, when the upcoming visit to Brazil of the New Age guru, promoted by the Holistic University of Brasília, was announced. The others, their natural complements as will be seen, were written now in February 1994, especially for this book. The appendices illustrate details that matter to the understanding of chapter II.

I recognize that, at least as far as Gramsci is concerned, the examination I present is superficial, that there would still be thousands of things to say that have not been said here.9 But someone has to start, and in the absence of better brains willing to digest the subject, it fell to me. As for Capra, he is far from representing the “New Age” in its entirety; although some see him as a synthesis of this movement, he is just one of its symptoms, albeit acute and sonorous. Therefore, no one should censure me for the incompleteness of these analyses: my samples bear the label of samples, with proud modesty. Also, this work has no pretension whatsoever to interfere in the course of things. Its only desire is to provide, to those who have a sincere desire to understand events, some means to do so. Now, those who have this desire are always few, amidst the clamor, enthusiastic or threatening, of those who believe they already know everything and who are impatiently waiting for the world to bow to their proposals. To those few and quiet, therefore, this work is dedicated. Among them, I highlight the novelist Herberto Sales, who read in typewritten version the first chapter and made generous references to it, which I thank with emotion. All the more moved because, if I had to choose a stylistic guru, it would not be another, in the present phase of our literature, other than Herberto Sales. I also highlight the brave group of students and listeners who have been following my work for years with an interest that comforts me.

Rio de Janeiro, February 1994.

I – Lana Caprina, or: The Wisdom of Mr. Capra

In the beginning of November10, Mr. Fritjof Capra will be arriving in Brazil, invited by the Holistic University of Brasília to speak about the New Age that he announces in his book The Turning Point.

Mr. Capra’s voice will not cry out in the wilderness. The Holistic University has already gathered a congregation of local intellectuals to say amen to him. Among the acolytes are Frei Betto and the former rector of UnB, Christovam Buarque. Mr. Capra, as you can see, is not a writer like the others: he is a leader, a spiritual authority and, let’s admit it, a prophet.

The content of his prophecies is well known: The Turning Point is even in the hands of children, who discuss it in schools. But, according to the Holistic University, this is not enough. Mr. Capra must be heard by all friends of the human species. Because, even though he shares a name with a filmmaker who became famous for his happy end films, he does not guarantee any happy ending for our century unless humanity follows his advice. Let’s therefore proceed to examine them, with the urgency required by the case.

According to Mr. Capra, the history of the world has reached a turning point, and must change its course. The three main changes at hand are as follows: first, humanity will stop consuming fossil fuels (oil); second, patriarchy will end; third, the current scientific paradigm will be replaced by another, holistic one. These three things are already happening, but, assures Mr. Capra, it is urgent to hasten their consummation, which will mark the advent of the New Age.

When talking about the first item, Mr. Capra is very brief, as befits prophets. Instead of the long analyses he grants to the other two themes, he only issues this prophecy: “This decade will be marked by the transition from the fossil fuel era to a new solar era, powered by renewable energy from the Sun”. Having the book been published in 1981, the decade Mr. Capra refers to ended in 1990. Well, not all prophets are lucky. But, if the mentioned prophecy is fulfilled four, five or nine decades late, Mr. Capra can always argue that St. John the Evangelist was not very accurate about the date of the Apocalypse either.

Like many other prophets, Mr. Capra can complain about being misunderstood. I, for example, do not understand how the world could have jumped directly from the fossil fuel era to the solar era, without passing through the atomic age, in which we were at the time of the prophecy and in which we continue to be after its due date. But perhaps Mr. Capra’s prophetic intuition operates at the speed of light, skipping stages. This is indeed a good reason to jump straight to the next item, since the first chapter of mutation did not have a happy end.

Patriarchy consists, according to Mr. Capra, of three elements: first, the domination of man over woman; second, the domination of the human species over nature; third, the predominance of reason (male faculty) over intuition (female). These are three sides of a unique phenomenon, which Mr. Capra summarizes as the supremacy of yang over yin.

As you can see, it is a special kind of patriarchy, quite different from the one we can find in history and sociology books. For these tell us that the increase in technical power over nature shook the rural property regime in which patriarchy was established; and that the advent of the Empire of Reason, brought about by the French Revolution, soon promoted equality of rights for men and women, dealing a merciful blow to the authority of the pater familias. In short, two of the three things that Mr. Capra groups under the common label of “patriarchy” are precisely the opposite. But prophets do not care about profane sciences. Non enim cogitationes meae cogitationes vestrae, the Bible had already warned us. Mr. Capra, indeed, does not think like us.

But there is something in him that at least some of us can understand perfectly well. Since logic, in his understanding, is an expression of the abominable patriarchy whose end he desires, he could not obey it without becoming, ipso facto, illogical. It is then for a simple matter of logic that he chooses to be illogical. Any baby can understand this. The difficult thing is to understand him when one is no longer a baby. To be admitted into the heavens of the New Age, the reader must therefore become like the little ones.

Here is a typical case. To rid ourselves of the hateful patriarchy, says our prophet, humanity should be inspired by the example of Chinese civilization, whose conception of human nature, especially expressed in the I Ching, “stands in stark contrast to that of our patriarchal culture”. Now seeking anti-patriarchal ammunition in the pages of the I Ching, the reader will find, in hexagram 37, the following recommendations: “The wife should always be guided by the will of the master of the house, that is, by the father, the husband, or the adult son. Her place is inside the house”. The life that Betty Friedan asked God for. Moreover, according to Marcel Granet’s classic La Civilisation Chinoise,11 Chinese feudalism, the period during which most of the I Ching commentaries were written, “rests on the recognition of male dominance”. The China that Mr. Capra refers to must therefore not be the same one that profane geographers know by that name.

What Mr. Capra really cannot be accused of is sinophile partisanship. For, if he rejects Western logic, he does not bow to the demands of the Eastern one either. According to him, the yang represents the analytical reason, which divides, and the yin the intuition, which unifies. The Chinese, understanding nothing of these subtleties, represented the divisive yang with a continuous line, and the unifying yin with a line divided in half. In the New Age, editions of the I Ching will come duly corrected.

While these editions do not appear, Mr. Capra is already taking care, on his own, of introducing some more serious modifications into Chinese thinking. For example, he says that in Chinese civilization, man does not seek to dominate nature, but to integrate himself into it. Once again, Mr. Capra’s Chinese wisdom caught China off guard: a Chinese person wouldn’t even understand this sentence, because in their language there is no word that means “nature” in the Western sense, that is, both the visible world and the invisible order that governs it (an ambiguity inherited by modern languages from the Greek “physis”). The Chinese language is, with all due respect, more “analytical” in this regard: it has one term to designate the visible world (khien) and another (khouen) for the invisible order. To compensate, the visible world or khien encompasses, “synthetically,” both the earthly nature and human society. Mr. Capra does not specify which of the two “natures” man should integrate into, but it is clear that no one could integrate into both simultaneously and in the same way. The ancient Chinese had already warned about this and resolved the contradiction by proposing a duality of attitudes to face this double aspect of nature: the sage, says the I Ching, must actively seek to integrate himself into the invisible order or khouen (called “active perfection”) and gently navigate the demands of earthly nature (khien or “passive perfection”). In other words, integrate into the celestial order, integrating the earthly order within oneself and dialectically transcending it (thus absorbing it in turn into the celestial order). In this sense, the “celestial” and the “earthly” respectively correspond to the dharma and karma of Hindu tradition. Man does not “integrate” into karma but “absorbs” it to the extent that he integrates into dharma: he frees himself from the weight of the earth to the extent that he heeds the celestial call. Christianity says exactly the same thing: man overcomes natural necessity to the extent that he follows the paths of Providence. That is not what Mr. Capra says.

The ideogram Wang (“the Emperor”) clarifies this better. It constitutes, by itself, a compendium of Chinese cosmology. It is composed of three horizontal strokes—the Heaven above, the Earth below, and man in the middle—forming the triad Tien-Ti-Jen, “Heaven-Earth-Man”—intersected by a vertical stroke, the Tao, which is somewhat conventionally translated as “law” or “harmony.” Harmony consists of each thing occupying its proper place, so that behind all the changes the world undergoes, the supreme order is not violated (although in this world of appearances it is necessarily violated, for as the Gospel says, “it is necessary that there be scandal”;12 but in the end, all partial disorders are reintegrated into the total order).

In the Chinese triad, man is called “son of Heaven and Earth.” Since Heaven is the father, it is easy to see, from hexagram 37, who is in charge. Therefore, man governs the visible world, but not on his own authority, but in the name of a transcendent order. Tien does not mean “sky” in the material sense, but the “celestial perfection” or more precisely the “will of Heaven”; in English, which Mr. Capra understands better, not the sky but heaven,13 the abode of the Holy Spirit. The sage or emperor apprehends the will of Heaven in the invisible and implements it on Earth. In the central hall of his palace, he performs daily rites of complex geometric and numerological symbolism (similar to Pythagoreanism), through which the celestial archetypes “descend” (just as in the Mass the Holy Spirit “descends”) to bring order and harmony to Earth. If the emperor ceases to perform the rites, the Earth—both society and nature—falls into convulsions, ignorance, fear, violence, hunger, and plague spread everywhere.

It was not only the interruption of the rites that could bring catastrophe. “The emperor,” writes Max Weber in The Religion of China, “had to conduct himself according to the ethical imperatives of the classical scriptures. The Chinese monarch remained essentially a pontiff. He had to prove that he was indeed the ‘son of Heaven,’ the ruler approved by the heavens, so that the people, under his rule, would live well. If the rivers burst their banks or rain did not fall despite all the rites, this was proof—explicitly believed—that the emperor did not possess the charismatic qualities required by Heaven.”

Man governs the Earth, but in the name of Heaven. He governs as a pontifex, a “bridge builder,” who links Earth to Heaven through the Straight Path, the Tao. If he deviates from the Straight Path, he loses sight of the Will of Heaven and can only rule in his own name, as a tyrant and usurper. Then, in a backlash, he loses his power and falls under the dominion of the earthly powers he once commanded. Since Earth designates both physical nature and human society, the clash can mean either a civil revolution or a military coup, as well as a storm or an earthquake. The fallen monarch represents, by analogy, any man who, by breaking with the celestial order, loses sight of his ideal destiny and falls prey to abyssal passions. This is the situation described in hexagram 36, “Darkening of the Light”: “At first, he rises to Heaven, then sinks into the depths of the Earth.” The traditional commentary, summarized by Richard Wilhelm, is as follows: “The power of darkness rises to such a high position that it can bring harm to all who stand on the side of good and light. But in the end, the power of darkness perishes by its own obscurity.”

It is clear that Mr. Capra’s advice, affected by the ambiguity of the word “nature,” can have two opposite meanings: by “integration,” does he mean that we should obey the Will of Heaven or that we should plunge into the depths of the Earth? When the words of prophets are obscure, they require interpretation. Let’s interpret.

In Mr. Capra’s version, Heaven is not mentioned. The triad is reduced to a duality: on one side, man, and on the other, visible nature. The male and the female. The yang and the yin. Each one is left with the alternative of subjugating the other or “integrating” into it. The man of industrial civilization opted for the first hypothesis. Mr. Capra advocates the second.

It is true that the Western civilization chose to dominate nature, as Mr. Capra says. But it is also true that, since at least the Renaissance, it has erased (just like Mr. Capra) any reference to a transcendent order (Tien) and left man alone, face to face with material nature. Since then, the history of Western ideas has been marked by a pendulum swing between the ideologies of domination and the ideologies of submission: classicism and romanticism, revolution and reaction, historicism and naturalism, scientism and mysticism, Promethean activism and quietistic evasion, Marxism and existentialism, and last but not least, socialist cultural revolution versus the ideology of the New Age.

It is in this last pair of opposites that the key to understanding our prophet lies. Mr. Capra hits the nail on the head (no prophet can achieve the miracle of always being wrong) when he says that his vision of cultural history is an alternative to Marxism. For Marx and his epigones, nature is nothing more than the backdrop of human history. It is there not as a “being,” an ontological substance that man must contemplate and respect in its objective constitution, but as raw material to be appropriated and freely transformed according to human whim. Nature, in Marx, is ancilla industriae. Marxism continues the revolutionary Promethean tradition of the Renaissance, enhancing it by fully and explicitly subjugating nature to history. This is what the ideology of the New Age opposes.

But it does not only oppose Marxism in general, but a specific form of Marxism that, like it, sought to bring about a “mutation,” a 180-degree turn in the orientation of human thought. The founder of this Marxist current was the Italian ideologue Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937). Gramscism proposes a cultural revolution that subverts all accepted criteria of knowledge, establishing in its place an “absolute historicism,” in which the function of intelligence and culture is no longer to grasp objective truth, but merely to “express” collective belief, placed outside and above the distinction between true and false. It is the total subjection of the “object” (nature) to the “subject” (historical humanity). In this new paradigm, the emphasis of scientific activity no longer lies in the objective knowledge of nature (the exact description of its visible appearance and the investigation of the invisible principles that govern it), but rather in its transformation through technology and industry. Correspondingly, in the realm of ideas, there is a kind of “permanent revolution” of all categories of thought that succeed one another in a vertiginous acceleration of historical becoming.

Against this, the ideology of the New Age arose. In response to revolutionary Prometheanism, it advocates “integration with nature”; against the acceleration of history, it proposes the “ecological” balance of the New World Order; and against absolute historicism, it heralds the “end of History.” Capra is inconceivable without Fukuyama. Capra is the shell, while Fukuyama is the core. All the flashy “esotericism” of the New Age, with its secret initiations, gurus, magicians, and rituals, constitutes nothing more than the exoteric, the external and social religious apparatus, whose interior, the “esoteric meaning,” is actually a very modern, rational, and secular science: strategic planning. Fukuyama is to Capra exactly what esotericism is to exotericism, as the Church of John is to the Church of Peter. But both, each on its own level and by its own means, fight against the same adversary.

Gramscism was very successful in the 1960s, inspiring the passing fever of Eurocommunism and revitalizing certain communist hopes. In Brazil, it conquered practically the entire left, and the Workers' Party (PT) is essentially a Gramscian party, whether it explicitly admits it or not. But the attempt at renewal was weak and belated: communism was ultimately defeated by the worldwide rise of the ideology of the New Age. After all, the mixture of quantum physics and Eastern symbolism, psychic experiences and free sex, promises of peace and mirages of self-realization offered by this ideology is infinitely more seductive than any “absolute historicism.” Brazil, always lagging behind, is one of the few places in the world where the battle still continues, with a fierce core of Gramscian remnants offering a quixotic local resistance to the triumphant armies of the New Age.

But if revolutionary Prometheanism represented the peak of hubris, of man’s dominion over nature, the ideology of the New Age is nothing other than the backlash announced by the I Ching.

The New Age has defeated the Gramscian revolution. But it was a teratomaquia: a combat of monsters. The Chinese would say that it was a suicidal struggle: that without common obedience to Tien, the struggle between Ti and Jen can only end in the “obscuring of the Light.” The victory of the New Age therefore heralds the next step in the cycle of mutations: humanity will fall from Promethean self-glorification into helpless passivity; it will “ecologically” integrate into the balance of the New World Order, where collective conformity will be ensured by the just distribution of means to satisfy the basest passions and by a semblance of external religiosity that will give these passions a flattering aura of “depth” and “self-knowledge.”

This can be interpreted psychoanalytically. Gérard Mendel, in his book The Revolt against the Father, one of the most important contributions of recent decades to Freudian psychoanalysis, says that throughout history, man’s impulse to overcome the father has been, as Freud claimed, one of the most powerful drivers of progress. But this impulse, he continues, can take two directions: either man overcomes and surpasses the carnal father by integrating himself into the rational order represented by the ideal father, or he disregards the ideal order altogether and, free from all moral constraints, kills the carnal father and takes possession of the mother. This latter alternative is the Promethean revolt, which is followed, in a backlash, by a fall into the irrational, a uterine regression, the “integration” of man into darkness. Hence, according to Mendel, the anthropological and also psychotherapeutic importance of the words of the most famous Christian prayer: the “revolt against the father” is only healthy and fruitful when undertaken “in the name of the Father.”

In Chinese terms, the carnal father is, for the adult man (Jen), nothing more than an aspect of Ti, the Earth. It must be subjected to the celestial order, Tien or the ideal father, so that man can then assume, without usurpation or violence, the just and harmonious governance of the Earth. I have always thought that Dr. Freud had something Chinese about him.

In Mendel’s terms, the Gramscian revolution is the destructive revolt against the father, and the ideology of the New Age, with its appeals to the fusion of individual consciousnesses in a soup of holistic illusions, is the uterine regression that follows it. All uterine regressions are heralded by an exacerbation of fantasy, the hypnotic call of senseless hopes, and the psychic foresight of endless delights. They all end in abject slavery, helpless passivity in the face of the aggression of abyssal forces, and the obscuring of the light.

It is inevitable that there be scandal. The New Age has defeated the Gramscian Prometheanism, and here comes hexagram 36. “There’s coming a shitstorm”,14 and Fritjof Capra is its prophet. But in the end, which certainly does not announce itself soon, the power of darkness will succumb under the weight of its own obscurity.

After the period of darkness, the Apocalypse assures, the madness of the new prophets who dragged humanity into error will be displayed in the full light of day, and everyone will see it.

As the New Age has barely begun, it is not time to do the complete show. For now, all we can do is give some preliminary samples, attesting to the reality of a past that will seem incredible to future generations. As the wise Richard Hooker said before the advance of Puritan nonsense in the 16th century, when all this has passed, “posterity will know that we did not let things happen like a dream through negligent silence.”

Mr. Capra’s book is full of such samples. But fairness demands that we select them according to the degree of importance given to them by the author himself. We must now examine the third “turning point”: the revolution of the scientific paradigm.

In this field, Mr. Capra does not seem to be at a disadvantage as in the Chinese world, which he only knew through third-hand sources. A doctor of physics from the University of Vienna, he cannot ignore the history of Western science as he ignores Chinese civilization. But who says he can’t? To the prophets, everything is possible.

According to Mr. Capra, "the paradigm now in transformation has dominated our culture for many hundreds of years"; it “includes a certain number of ideas” that “include the belief that the scientific method is the only valid approach to knowledge; the conception of the universe as a mechanical system composed of elementary material units; the conception of life in society as a competitive struggle for existence”. These conceptions have the respective names of: scientism, mechanicism and social Darwinism. I repeat: according to Mr. Capra, they have dominated our culture for many hundreds of years. This suggests two questions. First: what does it mean to “dominate a culture?” Second: how much is “many hundreds”?

We say that a certain idea dominates a culture when: first, it is believed by the most important intellectuals from all sectors; second, the competing ideas are either no longer fertile, that is, they no longer express themselves in powerful and meaningful works, or they have completely disappeared from the scene. Thus, for example, Christianity dominated the Middle Ages because, on the one hand, all philosophers and cultured men in general were Christians and, on the other hand, non-Christian currents of thought, although still alive at least in the collective subconscious, produced no work worthy of attention during this period. We say that Marxism dominated Soviet culture until the 1960s because during this period no eminent intellectual living in the USSR produced any idea outside the conceptual framework of Marxism, and because non-Marxist sub-currents (except in exile and in Western languages) created nothing significant.

In this strict sense, none of the three ideas that make up the “dominant paradigm” was ever dominant anywhere in the West. Since they appeared, all three have been incessantly contested, fought, refuted, rejected in whole or in part by important intellectuals. On the other hand, currents openly hostile to these ideas remained fertile enough to produce some of the most significant works in their respective fields.

Let’s look at mechanism. How can a current that, since its birth, has been rejected by giants such as Leibniz, Schelling, Vico, Schopenhauer, Driesch, Fechner, Boutroux, Nietzsche, Weber, Kierkegaard and many others, until it was overthrown in the 20th century by Planck’s theory, be “dominant”?

Strictly speaking, mechanism was only dominant, and even so with reservations, in a certain part of the world, which for Mr. Capra is “the” world: the Anglo-Saxon academic circles. That this traditionally presumptuous and self-confident little world is opening up to new ideas today, even being willing to listen to the Easterners without the traditional colonialist misunderstanding, is undoubtedly an auspicious novelty. But a local novelty. There is no surer way to make a people provincial than to persuade them that they are the center of the world. From that moment on, it declares everything that falls outside its field of vision to be nonexistent or irrelevant, and when it finally discovers something that the rest of the world already knew, it gives this discovery the air of a world revolution.

As for scientism, so much has been written against it that it is perfectly wrong to consider it dominant even in an attenuated sense of the term. To do so, one would have to exclude Marxism, psychoanalysis, phenomenology, neo-Thomism and existentialism, at least, from the foreground of culture. Here, again, Mr. Capra takes the opinion of a restricted group as globally dominant.

Social Darwinism, in turn, only became dominant, as a public belief, in a single country in the world: the United States. It never entered, for example, communist countries and the Islamic world, which together make up almost two-thirds of humanity. In Catholic countries, it was initially received as a perverse anomaly, causing scandalous reactions that are evidenced in the social encyclicals of the popes since at least Leo XIII.

But, besides affirming that these three beliefs “dominate the world,” Mr. Capra also asserts that they have done so “for many hundreds of years.” Let’s recount the history.

The oldest of the three is Mechanism. Foretold by Descartes, it was fully formulated by Isaac Newton (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, 1687), but only became known to the general European intellectual community from 1738 when Voltaire disseminated in layman’s language the Elements of Newton’s philosophy.

It was not only through scientific dissemination that Voltaire promoted Newton’s victory. He so slandered with crude irony Newton’s principal opponent, G. W. von Leibniz, that contemporaries stopped paying attention to what he was saying. Leibniz fell into almost disrepute until the 20th century when the rediscovery of his ideas caused prodigious advances in mathematics, logic, and the natural sciences. The new physics of Planck and Heisenberg turned out to vindicate Leibniz against Newton, replacing mechanism with probabilism. This replacement could have happened two centuries earlier if Voltaire, the emperor of public opinion in the 18th century, had not woven around Leibniz a web of lasting prejudices. Ironically, Voltaire entered History as the enemy of all backwardness and all prejudice.

But anyway, Voltaire’s opinion did not spread at the speed of light. It took two or three decades, at least, to become the dominant belief in all of Europe. By around 1780, Mechanism enjoyed an enviable prestige, and it could be said, since then, dominant, if dominant does not mean unanimously accepted or accepted without reservations. One must not forget the opposition that was moved against it by the vitalism of Goethe and Driesch, the contingencialism of Boutroux and many other currents, until the coup de grace delivered by Planck and Heisenberg.

At the moment Mr. Capra was writing The Turning Point, Mechanism was thus completing two centuries of incessantly contested glory and of precarious reign over the majority factions of the academic world. This is very different from a dominion of many centuries over the whole world.

As for social Darwinism, it is a product of biological Darwinism and could not have been born before its father. The principle of “survival of the fittest” emerged as a biological theory and only later, gradually, transformed into an ideological argument for the retroactive legitimization of capitalist competition.

The Origin of Species is from 1859. Herbert Spencer, in his First Principles, published in 1862, expanded the scope of evolutionary ideas, making them a sociological principle. At the same time, occultists like Allan Kardec and Madame Blavatsky picked up the term “evolution” and gave it a mystical or mysticoid meaning: it’s not only the amphibians that evolve into reptiles, and these into mammals; it’s the disembodied souls that, in the other world, evolve into “beings of light,” ascending the cosmic scale while monkeys descend from trees. Cloaked in a thousand and one meanings, the word “evolution” spread, and public debates arose, attracting intellectuals' attention to the political-ideological potential of evolutionism. The debates reached a peak of success with Thomas Henry Huxley’s lecture, “Evolution and Ethics,” in 1892. The way was then open for the legitimization of liberal capitalism by the “survival of the fittest.” The rest comes with the books of Gustav Ratzenhofer (Nature and Purpose of Politics, 1893) and William G. Sumner (Folkways, 1906), which explicitly underpin the notion of “social evolution,” giving capitalist ideologues the precious slogan they needed. Social Darwinism, therefore, has a little more or a little less than a century. It was even younger when Mr. Capra was writing his book.

Finally, Scientism. The formal and complete rejection, in the name of science, of any philosophical or theological explanation of reality, was proposed for the first time by Auguste Comte (Discourse on the Positive Spirit, 1844). But Comte still reserved for philosophy the task of synthesizing and ordering scientific knowledge, and Comte was accepted without contest in only one place on this planet: Brazil! (In 1914, the positivist Alain attributed the world war to the fact that no other country on the globe had followed Brazil’s example, which had adopted on the republican flag positivism as the official doctrine of the State: Order and Progress is, indeed, the summary of Comte’s philosophy). A formal and categorical declaration of Scientism, with the complete dismissal of all other forms of knowledge as empty or insignificant, only really came in 1934, with Rudolf Carnap, in Logical Syntax of Language. But Carnap was no Voltaire, to count on the immediate approval of a vast audience. The majority of 20th-century philosophers categorically rejected Scientism, which only exercised dominion over specific groups, especially in the Anglo-Saxon world. Contemporaneously with Carnap’s declaration, the mathematician and philosopher Edmund Husserl, founder of phenomenology — a school that would generate Heidegger, Scheler, Hartmann, Sartre, and Merleau-Ponty, among others —, gave at the University of Prague the famous lectures later collected in the book The Crisis of European Sciences, in which he denied Scientism from the base and from within: the physical sciences, he said, had lost their essential scientific foundation and no longer served as a model of knowledge of reality. Husserl was and is at least as influential as Carnap, although not so much in the Anglo-Saxon world that is the limit of Mr. Capra’s mental horizon.

In short, Scientism, which “dominates our culture for centuries,” is celebrating sixty springs in this year of 1994. But, to top it all off, its first ostentatious manifestation was already three decades later than the publication of Max Planck’s first works, whose indeterminism would become one of the bases of the “new paradigm” whose advent Mr. Capra has now come to announce. The new paradigm is somewhat prior to the old one.

Mr. Capra, as it can be seen, understands little about the subjects in which he exercises, as a prophetic authority for a multitudinous audience. He excels in lacking elementary information about Chinese cosmology, on which he claims to base his view of cultural history, as well as about cultural history itself, which he tries to forcefully fit into a preconceived model through gross generalizations and scandalous alterations of chronology.

I do not question the validity of the holistic proposal in general here. I reserve the right to do so in another work. I just believe that it should have defenders who are somewhat more qualified than Mr. Capra.

My purpose was to testify about a globally relevant fact that is happening right before our eyes, and future generations will have the right to doubt its reality. Because, for reason and common sense, it is not plausible that thousands of prestigious intellectuals, in their right minds, can accept and applaud a work like “The Turning Point” as a landmark in the history of thought, which does not even meet the minimum requirements of reliable information, authenticity of sources, and conceptual rigor that are demanded of a master’s thesis. Among the many other flaws a book can have, this one suffers from the only one that cannot be tolerated under any circumstances: the ignoratio elenchi, complete ignorance of the subject. Mr. Capra defines his book, pretentiously, as “a new model of cultural history” based on “Chinese conceptions” of man and the universe. But he has not studied cultural history or Chinese conceptions enough for his opinion on the matter to have any objective importance outside his personal circle. The content of his proclaimed knowledge on the subject is pure lana caprina.

The success of this book can only be explained by a single factor entirely unrelated to its intrinsic value: its timeliness. It says what people want to hear at the moment they want to hear it. It offers a seductive perspective to an audience that seeks to be seduced.

This audience includes not only uneducated masses but also prominent intellectuals, who readily accept the author’s promises without even demanding the scientific credentials required of a college student. It is truly an implausible occurrence.

But, as Aristotle said, it is not always plausible that everything should happen in a plausible manner. The implausible has happened. It attests that after centuries of iconoclastic fury directed against all past beliefs and the values of other civilizations, the educated opinion of the West has finally tired of being arrogant. However, instead of genuine remorse, it is staging before us a semblance of conversion, which reveals all the marks of hysteric feigning. Dazzled by the sudden sight of its own guilt, it renounces all critical caution as one would reject a vice of the past and surrenders, defenseless and credulous, to the worship of the first idol that offers a promise of relief. It thinks or pretends to think that this idol is its savior. In truth, it is its nemesis.

But it is not only the opinion that is deceived. The prophet of deceit is also deceived: he imagines that he brings wisdom to the world when he brings obscurity and confusion. He imagines that he brings a new prophecy when he fulfills an old curse.

But I cannot conclude these considerations on the prophet of the New Age without making a prophecy myself: in future centuries, when they can view our time with some objectivity, the phenomenon of the New Age will be considered a scandal that testifies against human intelligence.

The scandal is inevitable. Nothing can be done to avoid it. I will not even suggest, as Jesus did, that a heavy stone be tied to its bearer and thrown into the depths of the sea. Because, as hexagram 36 says, it is already at the bottom. All I can do is leave to posterity, if it comes across these pages, a personal testimony of these dark times: not everyone believed in the false prophet. 15

Addendum

Here is the translation of the text you provided:

There are countless errors and contradictions in Mr. Capra’s book, in addition to the ones mentioned. Pointing them out and correcting them all would require a voluminous commentary: a constitutive law of the human mind grants error the privilege of being briefer than its rectification.

But it is worth giving a few more examples so that the reader can see how fertile an error in the premises can be in its consequences:

1. Mr. Capra opposes the use of nuclear energy, even for peaceful purposes, but at the same time, he makes modern physics one of the foundations of the “new paradigm” he proposes. He separates physics as a modality of theoretical knowledge from the nature of its practical applications, as if one did not necessarily stem from the other.

In this regard, Mr. Capra is perfectly inconsistent with the holistic method he advocates. According to holism, any rigid separation between an idea and its practical manifestations is nothing more than an abstraction. Holistically speaking, the beneficial or destructive effects of nuclear devices must be rooted in the very modus cognoscendi that produced them. If Mr. Capra sees connections even between mechanistic thinking and the structure of the patriarchal family, how can he be blind to the much closer relationships between the theoretical content of a science and its practical applications?

2. In our society, Mr. Capra claims that entropic work (repetitive work that leaves no lasting effects, such as cooking a meal that will be immediately consumed) is devalued and therefore assigned to women and minority groups. He states that this devaluation is typical of industrial society.

In this case, should we consider tribal societies in the Upper Xingu, the city-states of ancient Greece, or European society in the Middle Ages as industrial societies? There has never been a society in which entropic services were more valued than others.

However, according to Mr. Capra, such a society did exist. He gives examples of Buddhist and Christian monasteries where cooking is an honor and cleaning toilets is an enviable merit. Will it be necessary to explain to Mr. Capra that a monastic order does not constitute a “society,” but rather a minority community that presupposes the existence of a society whose values it can oppose? If entropic work is valued within a monastery, it is precisely because it lacks value in the larger surrounding society. Humble tasks acquire spiritual and disciplinary value inside the monastery precisely to the extent that they have little social prestige or economic value in the “world.” The social devaluation of entropic work is not characteristic of industrial society but of human society in general. Conversely, its spiritual valorization is a distinguishing feature of spiritualized minorities involved in some form of religious rejection of the “world.”

3. “Traditions such as Vedanta, Yoga, Buddhism, and Taoism resemble psychotherapies much more than philosophies or religions,” says Mr. Capra. Well, if there is one characteristic trait of the modern West that radically distinguishes it from Eastern traditions, it is precisely the development of psychology as an independent science without any mystical or religious reference, and as a result, the effort to give a “psychological” explanation of all spiritual phenomena. By encompassing the spiritual traditions of the East within the concept of “psychotherapy,” Mr. Capra demonstrates the typical incapacity of the modern scientist to grasp everything in them that is purely metaphysical and non-psychological.