This book, for the poet Bruno Tolentino, is an essential part of Olavo de Carvalho’s philosophy, which can only be properly understood by taking into account the issues the author addresses with mastery in this collection of studies, skillfully cohered: symbolism and the mode of analogical reasoning, the relationship between poetry and philosophy, the mode of existence of literary genres and their species, metaphysics and the traditional worldview as the basis for artistic criticism – among other topics. Olavo applies and exemplifies the fundamentals he sets out in the first part of the book in a second part, composed of 3 film critiques and a theatrical one: he analyzes films acclaimed by critics, such as The Silence of the Lambs (winner of 5 Oscars), Sunrise (winner of 3 Oscars), and Central Station (nominated for 2 Oscars).

- Author’s Foreword

- Part 1 – Theoretical Studies

- I. The Symbolic Dialectic and Other Studies

- 1. The Symbolic Dialectic

- 2. Emotion and Reflection

- 3. Bernanos' Silent Glory

- 4. The Discreet Dynamiter

- 5. Learning to Write

- 6. The Art of Writing, Lesson 1: Forget the Writing Manual

- 7. Still on the Art of Writing

- 8. The Dogma of the Autonomy of Art

- 9. Poetry and Philosophy

- 10. Towards a Philosophical Anthropology

- 11. The Absent Question

- II. Literary Genres: Their Metaphysical Foundations

- Preface by José Enrique Barreiro

- Author’s Note to the First Edition (1991)

- 1. Statement of the Problem

- 2. Some Modern Opinions

- 3. The Mode of Existence of Genres

- 4. Ontological Foundations

- 5. Verse and Prose

- 6. Narrative and Exposition

- 7. Species of Narrative Genre

- 8. Species of Expository Genre

- 9. The Lyric Genre. Conclusion

- Table of Genres

- Part 2 – Films: Critical Studies

- I. Symbols and Myths in the Film “The Silence of the Lambs”

- Preface by José Carlos Monteiro

- Foreword to the First Edition

- 1. Terror and Pity

- 2. A False Lead

- 3. The Brain Behind It All

- 4. The Fascinated Fascinator

- 5. Brave Clarice

- 6. Essence and Accident

- 7. Stoicism and Christianity

- 8. Masculine and Feminine

- 9. Masters and Disciples

- 10. A Pair of Pairs

- 11. A Disturbing Partnership

- 12. Angels and Demons

- 13. Sheep and Goats

- 14. To the End of the World

- 15. Apocalypse and Parody

- 16. A Tip from Aristotle

- 17. A Little of Everything

- 18. Adapting the Novel

- 19. Imago Mundi

- Appendix 1: The Apology of the State

- Appendix 2: Plot Summary

- Appendix 3: The Hand Touch

- Appendix 4: Woman as a Symbol of Intelligence

- Appendix 5: Main Differences Between the Film and the Book

- II. The Crime of Mother Agnes, or: The Confusion Between Spirituality and Psyche

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- 1. The Plot

- 2. What it’s About

- 3. The Structure of the Play

- 4. Transfiguration of the Conflict

- 5. Mysticism and Dementia

- 6. Symbolism and Verisimilitude

- 7. Filling the Gap

- 8. Truth and “Fact”

- 9. Revelation and Miracle

- 10. Natural and Supernatural (1)

- 11. Natural and Supernatural (2)

- 12. Heaven and Hell

- Appendix

- III. My Favorite Film: Sunrise, by F. W. Murnau (1927). Cinema and Metaphysics

- IV. Central Station

- Credits

- About the Author

Author’s Foreword

A cultured man is not the one who returns from a disorganized and feverish day to a nocturnal orgy with Hegel or Bergson. Rather, it is the one for whom the daytime magic mirror, whether its floating images are bathed in sunlight or shipwrecked in shadows, offers a vision of the world that constantly becomes more and more his own. Philosophizing is not about reading philosophy; it is about feeling philosophy.

—John Cowper Powys

With this present volume, I begin to collect in thick-spined books the smaller writings that I have been leaving scattered throughout this world for two decades, in the form of booklets, course transcriptions, unpublished drafts, and discreetly or null circulated pamphlets.

Of unequal value, varying lengths, and diverse subjects, they have no other unity than that of the gaze which, as best it can, preserves its identity over time and questions everything around it, as it encounters things that cause wonder and give, according to Aristotle’s maxim, the occasion par excellence for the pursuit of knowledge.

I must explain that this gaze is essentially a philosophical gaze. Not believing in the pedantic clamor that makes a vain display of its own inability to define philosophy, but rather considering that there are valid reasons to see philosophy essentially as the pursuit of the unity of knowledge in the unity of consciousness and vice versa,1 I have in this a sufficient criterion to distinguish what is philosophical from what is not, and I would be a foolish donkey if I could not apply it to my own writings.

Therefore, it is not philosophical, even when ingenious and sublime, the essay that delights in variety as such, where consciousness dissolves in the flow of impressions, “undulating and diverse,” and doesn’t even bother to notice when it contradicts itself. Nor is it philosophical the one that presupposes the current consensus in a given area of human knowledge and argues based on it, assuming that its reasons will be accepted by those who share it. Much less so the one that, based on public opinion, uses language as an instrument of mere persuasion, however clever and subtle it may be. But it is philosophical and cannot be anything else, the essay that, amid the variety of themes and problems, seeks the opportunity to probe the founding principles of all certainty, like someone who systematically returns to the center from a thousand and one points on a circumference, even if chosen by chance. It is philosophical not by merit or lack thereof but by the nature of things, with the inexorable inevitability of a primary evidence or a tautology.

If you want to know, it was precisely my aversion to arbitrariness and aimless fashion that made me seek teaching far away from the Brazilian university. And when today someone, having read several of my writings or attended my courses, suddenly becomes aware of the unity of intentions that gives shape and meaning to everything I do and write—and in the same act apprehends the unity and meaning of their own pursuit of knowledge—at that moment, I thank Providence for preserving me from dispersion and university worldliness so that I would have the supreme joy of a teacher, which is to be able to open to his students a horizon much greater than the circumference of a dish of lentils.

The search for coherence, however, is only one aspect of philosophy. The other is the openness to the limitless horizon of experience, with all its variety and often irreducible confusion. It is accurate to characterize philosophy—complementing the above definition—as the permanent tension between experience and reason. But this tension is itself an experience, and there are more people willing to flee from it than to accept with an open heart the responsibilities it implies. Modernity as a whole, in a way, is an escape, as it begins by deactivating the tension by crystallizing its two poles into separate and self-contained “styles of thinking”—rationalism and empiricism—and inevitably ends up sacrificing human intelligence on the altar of a diminutive conception of both reason and experience, reducing the former to the mechanical operation of syllogistic technique and the latter to a conventional cut dictated by the “scientific method.”

The tension is permanent, but its poles shift places. Initially, the unity is purely internal, it is the potential unity of a nascent self that defends itself as best it can from external confusion. Gradually, it notices that it cannot persist without growing, that is, without absorbing, digesting, and transfiguring into rational expression what threatens it. There comes a point where the self itself becomes the focus of confusion, while the external world, with its demands and disciplines, helps it to rearticulate. Then the picture is reversed again, and again, until the periodic inversions are accepted as the very dialectics of life. This process is fundamentally identical in all human beings: the specific difference of the philosopher is that he yearns to consciously experience all the steps, not as a memoirist (although he cannot help being one in his own way), but as a witness to the universality of this experience.

Therefore, these are essays on philosophy. I only ask that in this expression, the term “essay” is not understood merely as a vague designation of a literary genre, but in the strict sense of a sketch and an attempt. Each of the works gathered here points and moves, in fact, towards certain principles' evidence, which, when organized and hierarchized, compose a philosophy. However, its full expression will not be found in this volume, for the simple reason that it is a philosophy in the making and that it could not be otherwise, given that its author is a man of sixty years—precisely the age when, after decades of essays and attempts, a philosopher begins to penetrate into the territory that will be definitively his own, if he lives to occupy it, by the grace of God.

Indeed, there is no precocity in philosophy as there is in poetry, music, physics, or religion. Every so-called young philosophical genius ends up refuting his youthful ideas, that is if he does not blow his brains out at twenty-one, like Otto Weininger. From Plato’s Republic to Husserl’s Krisis, all the masterpieces of philosophy are products of maturity and old age.

Philosophy is reflection, and there is no worthwhile reflection without the experience that precedes it. As Hegel aptly put it, the bird of philosophy only takes flight at twilight—a principle that applies to both individuals and civilizations.

For this reason, the descent into old age, which for most mortals is nothing more than the somber anticipation of decay after a triumphant climb, announces itself to the philosopher as the final journey towards the promised land after a life of toil and suffering, like entering a dome of light at the end of decades of struggle against darkness.

From where I stand, at the summit of more than half a century of existence, I can see, in a single intuitive glance, the entire horizon of evidence I have been seeking since my youth. But seeing them does not mean possessing them yet, since, by a curious fate inherent in the constitution of the human mind, the more intuitive and evident the content of knowledge is, the more it requires, to be expressed, the meticulous distinctions of dialectics and logic. A fate that, being unknown to those who still suffer from the dualism of thinking and perceiving, makes it impossible for them to understand philosophy as a symbolic form and as a masterful architectural art that, having as raw and almost tangible matter not words or sounds and colors, but rather what for the masses is the most abstract, that is, the pure eidetic schema of discourse, has as its inner form and ultimate goal that which, being supremely evident and luminous, is beyond all discourse.

It is therefore natural that the philosopher, before venturing to give his ideas the formal and systematic expression in which they will acquire their definitive identity, settles his accounts with the early stages of his life and work, like a painter who revisits and organizes his sketches before starting the painting.

This is the sense of the collection of Estudos reunidos that this volume inaugurates. For a writer, a critic, an essayist, a volume of this kind is the crowning achievement of a lifetime. Publishing it at sixty would be premature retirement. For the philosopher, it is only the time to make the final assessment of the essays to start the show.

All my work published to this moment, which this collection concludes, should therefore be seen as a long preface to História essencial da filosofia, to Breve tratado de metafísica dogmática, to Filosofia política, and other presentations that will follow, some of which are halfway to their final form, others dispersed and formless in class notes, others just in a nutshell.

Praying to God to give me the strength to complete the task undertaken, I present in this collection the reckoning of the early stages, not as one who contemplates the built house victorious, but as one who, seeing the materials gathered and organized—piles of bricks, mounds of sand, rows of boards—rolls up his sleeves to start the construction. Gathered and organized, it must be understood, only with regard to the validity of the ideas, for there was no concern for chronology or ordering of themes in the arrangement of these writings. I even preferred to select for this first volume some of the most recent ones, for mere convenience, because they seemed to me less in need of revisions and additions, and I did not hesitate to place them alongside a work like “A dialética simbólica,” from 1983, because in it, I believe to have prematurely achieved an expression that suits my current demands; and if his name appears on the cover, it signals the special joy I felt in writing it and even more so in subscribing to it now.2

As I present this volume to the public, I thank from the bottom of my heart all those who helped me preserve these texts, especially Meri Angélica Harakava, Stella Caymmi, Ana Maria Santos Peixoto, Maria Elisa Ortenblad, Fernando Carneiro, Henriete Fonseca, Marcelo Albuquerque, Denny Marquesani, Eduy César Ferro, Luciane Amato, Guilherme Almeida, Roseli Podbevsek, and my wife and accomplice, Roxane. If I have forgotten anyone, it was unintentional.

Richmond, VA, March 25, 2007.

Part 1 – Theoretical Studies

I. The Symbolic Dialectic and Other Studies

1. The Symbolic Dialectic

I swear by the rosy morning twilight;

by the night and all that it envelopes;

and by the full moon:

you shall pass from plane to plane.

(The Holy Quran: IV, 16-19)

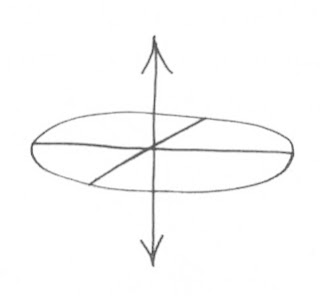

Seen from Earth, the Sun and the Moon have the same apparent diameter: half a degree of arc. However, all their other sensible qualities – color, temperature, etc. – are symmetrically opposite. This makes them the emblem par excellence of all maximum and irreducible oppositions, modeled by the scheme of two divergent and equidistant points from a central third point: on the occasion of the full Moon, the setting Moon and the rising Sun, or the rising Moon while the Sun sets, form the perfect image of the balance of opposites, with the Earth in the middle as the faithful balance.

This image naturally comes to mind when we want to evoke the idea of balance, in relation to, let’s say, the active and the passive, the masculine and the feminine, the light and the dark, or everything that Chinese culture summarized under the notions of yang and yin.

Being easy to remember and possessing great evocative and mnemonic power,3 it was natural that, in our time, the media appropriated it, using it as a tool to fix in the consumer’s imagination the message of new diets, fitness programs, and other ideological gadgets that entered the market through hippie naturism and pseudo-oriental doctrines. The abuse of the luni-solar emblem came along with the vulgarization of yin and yang.

Despite the vulgarization, the image and the notion it evokes are perfectly suitable for the reality they intend to express; the law of mutual compensation of opposites is not pure fantasy but a relationship that prevails in many planes and sectors of experience, and can be observed and abstracted from nature, for example, in the case of communicating vessels or acid-base balance. Within its limits, it is a perfectly valid explanatory or at least descriptive principle that works for certain groups of phenomena.

However, as soon as we move from the abstract concept of balance to the attempt to balance something real – for example, when we learn to ride a bicycle –, we find that our image of perfect symmetry breaks upon the impact of successive disillusionments: in fact, there is no perfectly static balance anywhere in the sensible world. Once the moment of balance is achieved, the central point slides, the whole escapes from fleeting symmetry, and falls; and we return to the oscillation of opposites, the variant undulation that does not form a fixed figure. Thus, in lived experience, in the succession of real moments, the point of balance is not really a point, but a line; and it is not even a straight line, but sinuous, swaying on the sides of a merely ideal axis, compensating the tensions from here and there, and composing with the play of imbalance of the parts, the pattern of the unstable balance of the whole – a pattern more imaginatively sensed than sensibly perceived.

In homeopathy, one often reasons in this way. An apparently alarming symptom – fevers, bleedings, suppurations – undoubtedly manifests an imbalance, but the clinician may refrain from medicating it if he believes that this partial imbalance of certain functions will contribute to restoring the balance of the whole organism. Conversely, a medicine that breaks a state of superficial balance can also be prescribed to induce, from the depths of organic roots, the ascensional formation of a new and more lasting state of balance.

Let’s agree that this reasoning is much more subtle and comprehensive than the previous one. It allows for a deeper understanding of phenomena. For example, if our pseudo-“oriental” “naturalists” were to study a little of the Hahnemannian method, they would eventually realize – better late than never – that there are no foods that are inherently yin or yang, but only foods that, in a given condition, temporarily assume, for a specific organism, the roles of yin or yang, roles that can be reversed with the further evolution of the situation. In fact, the Chinese tradition categorically affirms that the yin-yang dualism is “the extreme limit of the cosmos”; thus, it only truly exists on the plane of the total cosmos, and that individual entities are not only composed of different dosages of these two principles but that this dosage becomes progressively more complex as we descend from the universal plane to the most particular and sensitive planes. Thus, to evaluate whether any entity – let’s say, a turnip – is yin or yang, one would have to consider a practically infinite number of variables, including, obviously, the moment and the place, that is, the astrological factors involved in the case; which, all in all, shows the futility of such an endeavor. Such subtleties never escaped the Chinese. It is only the foolish rudeness of our “mass culture” that imagines it can squeeze cosmological concepts into dietary tables through shallow, linear, and ultimately entirely fictitious correspondences.

But, returning to the previous paragraph, what is the difference between the two reasoning processes we just described? In the first one, the two terms were statically opposed by equidistance from a center. However, if we move from the idea of static balance to that of dynamic balance, that is, from abstract concept to concrete experience, and thus realize that balance is not only made of symmetry and equidistance but also of interaction, conflict, and reciprocity between the two poles, then they are no longer opposites but complementaries. They are no longer just the extremities of a scale, but the matrices of a harmony, as indispensable and complementary to each other as sperm and ovum, bow and string, sound vibration and the vibratility of the eardrum. They no longer speak to us solely through their fixed equidistance, so to speak, crystallized in the sky, but through their coexistence, simultaneously hostile and loving, pregnant with tensions and latent possibilities.

Digging deeper into the difference, we find that, by changing the point of view, we introduce the variable time, or more simply, succession. Roughly, we can say that the first reasoning is a logical-analytical reasoning – or of identity and difference – and the second is a dialectical reasoning (in the Hegelian sense and not the Aristotelian). Those who consider themselves Hegelians have always accused the logic of identity of being purely static, aiming at formal abstractions rather than concrete things, immersed in the flow of time, subject to incessant transformations. Dialectical reasoning aims to grasp the movement, so to speak, of real transformations in the world of phenomena. The truth, according to this method, is not in the fixed concept of isolated entities but in the logical-temporal process that simultaneously reveals and constitutes them. This is the meaning of Hegel’s famous formula: “Wesen ist was gewesen ist” – “Essence [of an entity] is what [that entity] has become.” Or, in other terms: being is becoming.

In astrology, the symbol that evokes this second approach is that of the lunar cycle. It projects onto the celestial canvas the spectacle of permanence in change, of being that reveals and constitutes itself in becoming. In fact, it is the very mutations of the lunar face that eventually show man the unity of the source of light that, through the play of reciprocal and successive positions, creates this impression of change and variety: the Sun. Now, the Sun cannot be looked at directly. In Chesterton’s precious formula, “the one created thing in the light of which we look at everything is the one thing we cannot look at.” The Sun is thus an invisible luminosity. The Moon, on the other hand, can be seen with its clear profile outlined in the sky, but, to compensate, this profile is not constant. Thus, each of the apparent luminaries has something elusive, not to say ambiguous: one escapes direct sight because of its unbearable brightness, the other, due to its changing form, evades the static representation that preludes, in the sphere of the imaginary, what in the realm of reasoning will be conceptual crystallization. Now, the mutation of the lunar appearance clearly goes through three phases, or faces (the fourth face, the new Moon, is invisible): in the first, the Moon seems to grow as a source of progressively independent light. There it reaches a fullness: the full equivalence of two luminous circles of half a degree of arc appears in the sky. If the mutation were to stop at this point, we would say: there are two sources of light in the sky. But the moment of fullness already announces decline, already contains the germ of its suppression; and the waning comes, and finally, the Moon disappears: the Sun, which had remained constant under its luminous cover throughout this time, was revealed – to the observing intellect: was constituted – as the real single source of light, expressed and temporally unfolded by the ternary compass of its reflective surface, the Moon.

In spiritual symbolism,4 the Sun represents understanding, truth, and the Moon represents the mind, thought, the subjective image of truth: in dialectic, a latent truth is constituted in the human spirit by the process of becoming that reveals it, that veri-fies it.5

If the balance of the Sun and the Moon on the horizon, statically contemplated on the occasion of the full Moon, represented the static balance of opposites, and therefore the logic of identity and difference, the complete lunar cycle, contemplated in its temporal succession, prints in the sky the ternary movement of dialectical thought and the “ever-flowing” of natural things.

Dialectic reasoning is closely related to reasoning of cause and effect, to the idea of continuity of the same latent cause beneath the procession of effects, and also to the form of pure narration. Thus, the lunar cycle can represent either the dialectical approach or the causal-narrative approach indifferently. The ultimate sense of all historicism, in the broad sense of the word, is, in fact, to suppress the difference between logical order and narrative order.

If the reasoning of identity and difference6 is simple, direct, and molded in the observation of correspondences immediately presented to the senses or intelligence, the dialectical reasoning demands much more complex operations, such as the observation of an entire cycle of transformations.

Thus, there has been a transition from one plane to another, an upward movement: when we pass from static opposition to dynamic complementarity, from static reasoning to dialectical reasoning, we change our observation point, and a new system of relationships becomes evident in the spectacle of things. We feel that we have come closer to “effective reality,” abandoning a merely formal schema and freeing ourselves from subjective confinement. We seem to have found a solution to the opposition initially posed: by introducing the variable “time,” opposition has been resolved into complementation.

However, upon careful examination, we find that dialectic has only solved one problem at the expense of creating another: by resolving the opposition between the Sun and the Moon, it has installed in its place the opposition between the static and the dynamic. While it is true that many static oppositions can be resolved through dynamic reasoning, it is no less true that none of them can be initially established except by the static and abstract formulation of the concepts of their elements. How could we dialectically “fluidify” the opposition between the Sun and the Moon if we did not know what the Sun and the Moon are, that is, if the concepts of these two celestial bodies were not fixed? From now on, we are condemned to a radical duality, which separates thought and reality with an iron screen: our concepts will always be static, reality will always be dynamic. Dialectic leads to the dualism of Bergson7 and Bachelard.8 The synthesis decomposes into melancholic antinomy.

To make matters worse, dialectic itself, to take action, has to introduce new concepts, which will also be static, including the concept of dialectic itself. These concepts can then be dialecticized in turn, and so on endlessly. But, as Heraclitus, the grandfather of dialectic, said, “we never step into the same river twice,” we may wonder if this statement by Heraclitus has the same meaning twice.

Dialectic is thus faced with a tragic dilemma: to choose an endless discourse – which, having no limits, ceases to have any identifiable content, as noted by the neopositivist critics of Hegel9 – or to arbitrarily and therefore irrationally determine an arbitrary endpoint for the dialectical process. Hegel, as is well known, made himself the endpoint of the history of philosophy, and philosophy continued to exist after him.

Therefore, it is urgent to move beyond dialectic, to climb one more step, to rise to a broader and more comprehensive perspective. And once again, it will be the celestial model that will come to our aid, following Plato’s warning that without orienting ourselves by the lines of divine intelligence crystallized in the planetary cycles, our thoughts continue to wander from error to error.

It happens that the two poles of our initial opposition can only be called contraries – or, subsequently, complementaries – when viewed in the same plane, that is, when measured by the same standard, resulting in equal quantities.10 In the transition from static to dynamic reasoning, something certainly changed – the mode of representation – but something remained the same: the observer’s point of view;11 in both cases, we assumed that the observer was stationed on Earth; first, contemplating the moment of balance between the Sun and the Moon on the horizon; then, following the cycle of transformations during a lunar month; but always from the same location.

All oppositions – and, therefore, all complementarities – are based on some common trait, which is inversely polarized in one element and in the other. Oppositions are accidental differences resulting from a background of essential identity; complementarity consists only in reconstituting this background of essential identity, which a moment of the process had veiled, and which the temporal observation of the complete process unveils again, just as the Sun and the Moon can obscure each other during an eclipse and then reveal themselves as they really are. This play that moves from identity to difference and back to identity can only unfold before a static observer firmly stationed in their observation post.

Now, humans cannot normally leave their observation post; they cannot physically transport themselves outside of the Earth. They can only travel mentally; but, left to itself, the imagination wanders among celestial spaces and falls into formless fantasy. The antidote to this danger is astronomy: through accurate measurement, humans restore the true figure of the heavens in their representation, and they already have the support of a new intellectual model – based, according to Plato, on divine intelligence – to seek a point of view that allows them to go beyond common dialectics, penetrating into what we could call symbolic dialectics.

If, in common dialectics,12 we introduced the factor “time,” here we will use the element “space,” thus completing the model on which our representations and the sensitive models of their respective forms of reasoning are based. We can say that the dialectical point of view corresponds to a merely “agricultural” observation of the heavens: all it captures is the idea of transformation and cycle. The symbolic dialectic will now start from a properly astronomical understanding and delve into the spatial interweaving of various points of view and the various cycles they unveil.

Now, if we abandon the terrestrial point of view and consider the solar system as a whole,13 that is, the larger framework of references in which the various elements come into play and differentiate, we find that, in reality, the Moon is not opposed to the Sun, as in the static identity reasoning, nor coordinated with it, as in dialectical reasoning, but rather subordinated. In fact, it is even doubly subordinated, being the satellite of a satellite. The Earth is to the Sun as the Moon is to the Earth. Thus, we form a proportion, and here, for the first time, we achieve a fully legitimate rational approach, since “reason,” ratio, originally means nothing more than proportion.14 It is the proportion between our representations and experience, and between reasoning and representations, that ensures the rationality of our thoughts and, ultimately, the truth of our ideas.

Having reached this point, immediately the initial opposition and the complementarity that followed reveal themselves as partial aspects – hence insufficient – of a set of proportions that eventually merge into the unitary principle that constitutes them. Because all proportions, as we will see later, are variations of equality, just as the interactions between the angles and positions of the various planets with each other are absorbed and resolved into the positioning of all around their central axis, which is the Sun.

This third modality is called the reasoning of analogy.15 There are many current misconceptions about what analogical reasoning actually is. For example, many authors believe it to be the mere observation of similarity of forms.16 Others assume it to be a primitive and vaguely “poetic” form of assimilating reality, radically distinguished from rational and logical apprehension.17 Analogy is confused with similitude, metaphor, allegory, and many other things, and its cognitive value is mistakenly underestimated. Few modern philosophers demonstrate a mastery of analogical reasoning as practiced by the ancient and medieval thinkers; it seems that the majority does not quite understand what it consists of.

If academic philosophers make mistakes in this regard, their traditional adversaries, astrologers, and occultists, make no fewer. They do so, however, with the opposite intention, emphasizing the superiority of analogical reasoning. In fact, they use and abuse a famous “law of analogy,” called upon to legitimize their art, and whose function is to unite, in synchronous pulsation, the whole and the part, the universe and the individual, the distant and the close, everything that fits into the classic formula of the micro and the macro contained in the Tabula smaragdina attributed to Hermes Trismegistus.18

However, it is not the place here to criticize astrologers; the fact is that they interpret this “law” in a flat, shallow, linear manner, as if there were not merely an analogy but an identity between the micro and the macro; for example, when reading horoscopes, the correspondences they see between celestial configurations and events in individual human life are practically direct, without the modulations and mediations that common sense requires, and without the inversions of meaning that the very rule of analogical reasoning, when properly understood, demands. For instance, having established a symbolic connection between Saturn and fatherhood, and between the Moon and motherhood, they will directly interpret an “inharmonious” angle19 between Saturn and the Moon in the natal chart as an indication of a conflict between the consultant’s mother and father. This grossly mechanical form of reasoning was aptly caricatured in a “syllogism” invented by the Spanish astrologer Rodolfo Hinostroza:

"Saturn = stone. Sagittarius = liver. Therefore, Saturn in Sagittarius = stone in the liver. Or, if you prefer, stoning in the liver."20

Likewise, they establish direct correspondences between Libra, as a symbol of cosmic balance, and common justice in our courts, between Taurus and bovine laziness, and many others in the same vein and of the same value. However, astrology is a cosmological symbolism, not psychological: the plane where its phenomena unfold, the stage where its drama is played out, is the total cosmos, not just the individual’s mind, let alone the mental theater of middle-class women who are the typical clients of astrologers. Between these two planes, separated by many “worlds,” there must necessarily be many transitions and attenuations; I will explain this later. What matters to note now is that analogical reasoning is a subtle tool, one of precision: it cannot withstand being flattened and compressed, merging the macro into the micro.

What does analogy actually mean? Firstly, any Greek dictionary will indicate, under the entry αναλωγος, analogos, the sense of “proportionality,” in the sense of the formula

a/b = x/y

or in the sense of the harmonies between the different lengths of strings on a musical instrument and the sounds they respectively emit when vibrated. Proportions, as it is obvious, consist precisely in the ratio of differences between different values. Therefore, if there are no differences, there is no analogy; there is simply identity, in the sense of the formula

1/1 = 1/1

or, to sum up, 1 = 1. This should reveal from the outset that, in the symbolism of spiritual traditions, unlike what happens in today’s consultative astrology, any astral symbol – planet or sign, angle or house – could never have the same meaning when considered in different planes of reality, for example, in the plane of the total cosmos, that of historical cycles, and that of individual psychology. Secondly, the prefix ανα, ana, which forms this word, signifies an ascensional movement:

μελανες ανα βοτρυες ησαν

Mélanes aná botrües esan:

“Above, there were black grape clusters”

(Iliad, 18:562)

It is translated as “on,” “above,” “upstream,” “upward,” as in anagogê, αναγωγη, “elevation,” “action of elevating or snatching upwards,” or as in anábasis, anaforá, etc.

The term “analogy,” therefore, suggests that it is a relationship in an ascending sense. Or, more accurately: the two objects connected by a relationship of analogy are linked from above: it is through their higher aspects that beings can be “in analogy.” An analogy is all the more evident the further we move away from sensory particularity to consider beings under the aspect of their universality. Correlatively, this relationship fades away the more we look at beings from their lower aspects, from their empirical phenomenality, precisely the plane where, despite their lofty claims, astrologers and occultists operate.

What establishes an analogy between two entities, therefore, are not the similarities they present on the same plane, but the fact that they are connected to the same principle,21 each representing symbolically its own way and level of being, and containing in itself both, is necessarily superior to both. It is at this level of universality that the celestial bond of analogy is celebrated, connecting in a chain of symbols gold to honey, honey to the lion, the lion to the king, the king to the Sun, the Sun to the angel, and the angel to the Logos. Viewed from above, from the principle that constitutes them, they reveal the proportionality between the symbolic functions they perform for the manifestation of that principle, each at the cosmological level to which it corresponds, and this proportionality constitutes the analogy. Viewed from below, from empirical phenomenality, they disintegrate into the multiplicity of differences. Thus, analogy is simultaneously evident and ungraspable; obvious to some, inconceivable to others, depending on the unity or fragmentation of their respective worldviews.

Therefore, we use analogies to ascend from sensory perception to the apprehension of spiritual essence, to move from the visible to the invisible, or, in the terms of Hugo de São Vítor,22 to move from nature to grace: nature, the sensible world, “signifies” the invisible; spiritual grace “exhibits” it, at the top of the ladder. The ladder of analogies – evoked, for example, in Jacob’s ladder, in the steps of Paradise in Dante, and in all hierarchies of spiritual knowledge – is a means of access to the principle, and on the other hand, it collapses if this principle is removed from the top where it hangs.

Being a vertical and ascensional bond, analogy differs from simple relations of similarity – complementarity, contiguity, contrast, etc. – that relate, join, separate, and order entities on the same horizontal plane. This distinction, however elementary it may be, easily escapes the modern observer, as even a discerning historian like Michel Foucault is mistaken in classifying analogy as one of the forms of similarity in medieval science. In reality, the difference in planes between these two relationships does not allow them to be seen as species of the same genus, just as hierarchical classifications in general differ from typological classifications: the distinction between captain, major, and colonel is not of the same kind as the difference between infantry, artillery, and cavalry.23 And even less could analogy be subjected to similarity, as species to genus, just as one could not say that the classification of military ranks is a species from which the division of the three arms constitutes the genus.

This should be enough to demonstrate that certain resemblances that astrologers point out between planets (or planetary myths) and entities and events in the terrestrial world – such as, for example, the fact that Mars and blood are both red – are not analogies because they do not refer to the principle that constitutes these two entities and that is the common reason for their similarities and differences. These are mere similarities discerned on the same plane (in this case, that of chromatic sensory qualities). And as, in the descending sense, the relationship of proportionality progressively dissolves into the multiplicity of differences, these mere similarities may be quite insignificant and even entirely fortuitous; and no serious knowledge could be obtained by collecting curious coincidences.

In the symbolic scheme we are studying, the transition from the particular to the universal is symbolized by the transition from the geocentric viewpoint to the heliocentric viewpoint. The latter, due to its greater scope, allows us to grasp relationships – analogies – that the particularism of the terrestrial view obscured. Summarizing the phases traveled, we go through: 1st phase. Viewpoint: momentary sensory appearance. Reasoning: identities and differences. 2nd phase. Viewpoint: temporal and cyclical. Reasoning: causal or dialectical. 3rd phase. Viewpoint: space-temporal, comprehensive, universalizing, ascensional. Reasoning: analogy.

On the other hand, if analogies lead to knowledge of the principle, it is because this knowledge already resided in us in a virtual way. This latent presence, this invisible guide that leads us with a sure hand through the “straight path” of analogies in the forest of similarities, is symbolized by Virgil, Beatrice, and St. Bernard in the three stages of the poet’s ascent in Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Now, in general, we only know the universal principles in their abstract formulas, so we often find ourselves divided between a universal truth detached from concrete experience and a concrete experience devoid of truth and meaning, reduced to the most blind and tedious empiricism. The climb of analogies aims precisely to bridge this gap, leading, as far as possible, to a lived and concrete knowledge of the universal. Through analogy and symbolism, as well as through the many spiritual arts, sciences, and techniques that aim to crystallize and condense this symbolism in subjective experience, the goal is precisely to transform and expand the individual psyche so that it itself reaches a universal dimension, in the image of the Universal Man,24 which is the compendium and model of the entire cosmos.

In numerical symbolism, all proportions are, ultimately, forms and variations of identity. Identity is a single, simple, and abstract formula, 1 = 1, which synthetically contains all the proportions of the universe, that is, all the “dosages” that compose things and beings. By knowing the principle of identity, we know, in a sense, the reason of all reasons; it is universal knowledge, but still in a virtual and abstract mode, like a seed that potentially contains an entire forest. The ascent of analogies gives living concretion to this principle, summarizing, so to speak, in an abbreviated manner, the entire range of possibilities contained in the principle of identity, and at the top of the ladder, we rediscover this principle, no longer as an abstract formula but as full reality, as the sense of truth and truth of sense, as the unity of truth and sense. It is only in this way that we understand what scholasticism called concrete universal, a synthesis of logical universality and existential fullness.25

This reunion, this re-connection, resonates as the full realization of the meaning of life. It is the reunification of man with himself, preliminary to the reunion with God. In the philosophy of Hugo de São Vítor,26 it is the reunion of the outer, or carnal, man with the inner, or spiritual, man. Hugo, following a tradition but translating it with genius and originality, first distinguishes four levels in man: in the corporeal part, sensus (senses) and imaginatio (imagination); in the spiritual part, ratio (reason) and intelligentia (intelligence). Then he asks: is there not an intermediate level, a link between spirit and body? To this intermediate level, Hugo gives the name affectio imaginaria, and his disciple Richard of St. Victor calls it imaginatio mediatrix; “imaginary affection” and “mediating imagination.” It is in this intermediate level that the knowledge of analogies and symbolism, in general, takes place, and it is there that the reunion of universal truth with and in concrete experience occurs. The ontological counterpart of this psychological level is the so-called mundus imaginalis, the world of imaginal forms, which should not be confused with the imaginary (Hugo attributes the imaginary to the corporeal part) and which constitute the lost link between the world of the senses and universal concepts; it is there that the reunification of man with himself is celebrated, and it is there that we must turn our attention if we want to break the divorce of soul/spirit that four centuries of Cartesianism have accustomed us to. If the reasoning of analogy is so incomprehensible to modern man, it is because he has lost sight of this intermediate world, becoming accustomed to understanding as “abstraction” everything that escapes the realm of the senses. But this intermediate world is not only the world of symbols, but also of imaginal entities symbolized by them, for one could not conceive a cognitive faculty that did not have its objective counterpart, its own and independent object of knowledge. And it is in the imaginal world that we find again the angels and all the characters of biblical and mythological narratives, as forms of reality that are not reduced to our subjective psyche or to a merely external objectivity.27

Without the climb through the imaginal world, without symbolic dialectics, the human mind will always be divided between empirical particulars and abstract universals, unable to rise to the knowledge of the infinite unity, which, upon careful examination, is the only concrete reality from which everything else is an aspect or a fragment obtained only through abstraction. This climb coincides, in large part, with that described by F. W. Schelling, in which sense (knowledge of particulars in indefinite number, without unity) and understanding (knowledge of abstract unity) ascend to reason (knowledge of concrete unity and infinitude) through imagination. At the top, the affirmation of identity is always found:28

The affirmation of infinite unity is not accidental to reason; it is its total essence itself, which also expresses itself in that law that is accepted as the only one that includes an unconditional affirmation: the law of identity (A = A).

Until now, you have considered this law only as formal and subjective, and you have only recognized in it the repetition of your own thought. But it has nothing to do with your thought; it is an infinite universal law, which asserts from the universe that there is nothing in it that is purely predicative or purely predicated, but that there is eternally and everywhere only one thing that affirms itself and is affirmed by itself, that manifests itself and is manifested by itself; in short, that nothing is truly unless it is absolute and divine.

Consider this law in itself, know its content, and you will have contemplated God.

The climb ends there. At the top, we find again the superior principle that organizes the various levels of an analogical sequence, and it seems that there is nothing else to know in this domain. We may have the illusion of having once and for all reached the supreme truth.

However, in practice, the closer we get to a universal principle, the further behind and far away the concrete realities whose explanation we sought become. And near the top, we sometimes seem to have lost sight of the purpose of the journey. The moment of reunion passes, and all that remains in our hands is the abstract and lifeless statement of a logical principle, which is the melancholic remembrance of a lost universality. Therefore, it is necessary to descend again from the principle to its particular manifestations, and then climb again, and so on. So the alternation of yes/no, truth/error, which is the beginning of our investigation, is finally replaced, in a turn of ninety degrees, by the alternation high-low, universal-particular. We move from horizontal oscillation to vertical. And it is precisely the awakening of the ability to constantly perform the ascent and descent that constitutes the objective of all spiritual education, without which the perspective offered to us by symbolic dialectics becomes only a mirage. We thus understand how vain and childish any philosophy teaching that remains at the level of mere discussion and does not include a discipline of the soul is. The fact that philosophy has descended from the condition of inner asceticism to that of mere confrontation of doctrines in an environment of worldly gossip is a malady from which the West, perhaps, will never recover.

2. Emotion and Reflection29

Emotion recollected in tranquillity is certainly not a definition of poetry or art in general, but it is the statement of one of the basic requirements for its exercise. It does not express its essence but a condition of its existence. It is not a proposition of aesthetic theory but of the psychology of art.

However, the word “art” in this case must be understood in a broader sense than in the usual academic division of disciplines. It must also extend to the “humanities,” and in such a way that they also encompass “philosophy” and even, to some extent, the so-called “human sciences,” without excluding altogether, from certain aspects, the (improperly called) “natural” and “exact” sciences. It must encompass, to a certain extent, the entire realm of human intellectual creations, to the extent that these cannot emerge from nothing without some spiritually emotional experience giving initial impetus to the inner creativity of the artist, philosopher, or scientist, and they cannot find the conditions for their full formal manifestation without the subsequent retreat that recalls this experience and elaborates it in the tranquility of reflection.

“Reflection” here does not necessarily mean internal dialectics, rational critique of the experienced life; in a more elastic, but not imprecise sense, it designates the simple inner, conscious, and deliberate return to experience, whether to reproduce it with greater accuracy, to complete it, or to alter it. What distinguishes the reflective moment from direct interior experience is the conscious intention to fix it, be it in an image, in musical notes, or in words, whether those words are, in addition, allusive symbols or rigorous terms that grasp it in the delimitation of its essential concept. Now, this intention goes precisely in the opposite direction of the living flow of experience; it is a spiritual and intentional return to that which, in a real and material sense, never returns.

For this reason, it has always seemed to me foolish and mere posturing the pretension of artists who claim to capture the living experience and consider themselves wiser for it, almost like prophets or angels, compared to the philosopher or scientist who grasps from it only the “dry” and “dead” scheme of a “concept,” a contemptible thing. For the “living experience,” if it does not come in the form of a concept, does not appear in meter or musical notes either, but is transformed into them by the art or artifice of the artist, who, in doing so, distances himself from it, moving towards the spirit, just as the philosopher or scientist does, distinguishing themselves only by the different genre of schematization or formalization they employ.

But notice that, in the lines above, I did not refer to direct and raw experience, but rather to an already spiritualized and valued experience. No one who knows the subject will deny that the experience of the world of a true artist, philosopher, or man endowed with inner richness and depth differs significantly from that of the ordinary person. While in the latter, everything is resolved in an empirical equation whose terms are pleasure and pain, advantage and disadvantage, in the exalted soul, experience, however small, always indicates something that goes far beyond experience; the particular is a sign of the universal, and experience, however direct and raw it may appear at the moment it happens, already brings in the background the element of contemplative withdrawal that ennobles and values it with a meaning that transcends immediate empiricism, due to the greater diameter of the inner space where it takes place: “Mon cœur profond ressemble à ces voûtes d’église, où le moindre bruit s’enfle en une immense voix” (“My deep heart is like those church vaults, where the slightest sound swells into an immense voice”).

Now, the profound and sensitive man to whom I refer, if he obtains a richer harvest of interior repercussions from the experience, it is not because he deliberately enters it with the intention of making it the material for paintings, poems, or philosophical systems, but simply because he already is who he is, a poet or philosopher with a poet’s soul, already formed by the long series of determinations that may come from an ancestral destiny, and consolidated in his vocation by the succession of experiences and purifications that have prepared, precisely, the inner stage where this particular experience comes to penetrate at a given moment.

In an era when literature and philosophy have become names of professions, whose legal exercise is accessed through public examination and the state’s gracious concession, under the protective care of class unions, it is not excessive to remind you that the true poet and the true philosopher are not distinguished from other human beings merely by their greater capacity to elaborate, respectively in rhymes and in syllogisms, contents of consciousness which are as banal in their nature as those of a civilian. On the contrary, they stand out from the latter because they perceive as real and immediate certain subtle relations that appear, or would appear if spoken of, far too distant, abstract, or entirely fanciful to him.

But even this differently differentiated spiritual experience does not come in the form of a book, a painting, or a symphony. It must be transposed through subsequent work of remembrance, selection, ordering, etc., which can ultimately transform it into something very different and much richer or poorer than it was at the moment it occurred. Hence the term “work of art,” which means: the fruit of human labor, never a gratuitous gift of nature.

Moreover, there is no specific difference between the spiritual experience of the poet, the musician, the philosopher, or even the true scientist. In all these cases, it is a matter of perceiving, behind the amalgam of immediate data, the hint of a meaningful form, as if life itself were speaking.30 The difference lies in the various codes that subsequently serve as guides and patterns for the reflective elaboration of the residue of experience preserved in memory.

Each of these codes is constituted by a set of requirements consolidated by a long tradition of work, requirements that determine and select the different conditions of communicability and credibility of the “contents” of experience. Some of these requirements may be entirely conventional, others may result from a progressive purification of artistic, scientific, or philosophical consensus; others may be based on common sense or universally accepted principles. It matters little: the fact is that, when transforming personal experience into a communicable form, the creative subject must take them into account.

The very prototype of the inner experience to which I refer is that mentioned by Aristotle: "Those who go through an initiation are not there to apprehend something with their understanding, but to undergo an inner experience and be placed in a certain disposition…"31

It is evident that this inner experience cannot be reduced, on the one hand, to the banal sensory experience32 of the natural and civilized man, nor, on the other hand, inflated until it becomes indistinguishable from the finished products of subsequent elaboration. It is precisely halfway between raw experience and consciously created form. It is the indispensable precondition for all artistic, scientific, or philosophical creation, preceding and indifferent to these differentiations of discipline names.

That is precisely why, in judging the creations of intelligence, one can take into account not only their more or less perfect elaboration but also the breadth, coherence, and quality of the inner experience that serves as their foundation. This experience constitutes the “world” of the philosopher, the artist, the scientist, a world that, considered in itself and independently of the subsequent reflective effort that gives it shape and makes it participable by other human beings, can be richer or less rich, more integrated or less integrated, more profound and comprehensive, or less.

Few inner universes are as well elaborated and formalized as those of Wittgenstein, Maurice Ravel, Mondrian, Paul Valéry, or Stephen Hawking; but they cannot be compared, in breadth and depth, to those of Louis Lavelle, Wagner, Picasso, Eliot, or Heisenberg. If there is a sense in distinguishing between “content” and “form,” it is when taking the form of the spiritual experience as such as a synonym for “content,” prior and independent of the concrete form of the “work,” behind which it can be perceived in filigree (by those who, of course, possess similar or better experience).

Note that in all these cases, the qualitative judgment of the spiritual experience transcends and abolishes the differences between the formal disciplines (physics, music, poetry, etc.) that served as the mold for its incarnation in historically recorded works.

It is not necessary here to take the word “initiation” in the strict and conventional sense of belonging to a brotherhood of mysteries and submission to traditional rites officiated by flesh-and-blood hierophants. The spirit blows where it wills, and no secret order or public church possessing the monopoly of divine inspiration, it is predictable that, the more corrupt and exhausted churches and secret orders become, the more cases of spontaneous inner experiences and direct communication between Sense and the soul will multiply.

Now, it remains to explain the nature of the diverse elaboration that the poet, philosopher, physicist, etc., undertake according to the demands of their respective trades.

That one spiritual experience can be quite similar to another; that experience as such cannot bear the mark of the differences between art and philosophy, science, and religion, is something proven by the fact that the inner universes of two men of different intellectual professions can be much more related to each other than those of two men of the same profession. Dante’s universe is more similar to that of Saint Thomas than to that of Petrarch, despite the differences in the concrete form in the first pair and the similarities in the second; the world of Saint Bonaventure, shaped in the form of a theological treatise, is the same as that of the poet Saint Francis of Assisi but quite different from that of his fellow workers (and literary genre companions), Albert and Thomas.

The affinities of “content,” in the sense of the community of spiritual experience, transcend not only the differences from one discipline to another, from one genre to another, but even the diversity of ideas and personal convictions: Dostoevsky’s world has more affinities with Freud’s than with that of his contemporary and colleague Turgenev, and Freud’s, in turn, resembles more the theater of Schnitzler than all the clinical psychiatry of the time. Similarly, Bergson and Proust are closer to each other than the former is to Brunschvicg and the latter to Gide, their contemporaries and colleagues.

Examples could be multiplied indefinitely, but one would be enough to show that there is no bond of reciprocal implication between the nature of the spiritual experience and the modality or genre of its concrete expression in the forms of recognized cultural disciplines. The inner history, the spiritual history of humanity, does not coincide with the history of forms or disciplines, much less with the "history of ideas."33

3. Bernanos' Silent Glory

The year of the fiftieth anniversary of Georges Bernanos' death has ended, and no one wrote anything about the great exile in the country he chose as his second homeland, where he wrote some of his most forceful books – Lettre aux Anglais, Les Enfants Humiliés – and where he had more friends than in his native land.

The silence is perhaps explained by the simple fact that Bernanos dead is even more uncomfortable than he was in life. There is no one more troublesome than the one who is right. Usually, time reveals who is right, and the truthful minority, temporarily defeated by dominant lies, eventually has its day of revenge. However, in Bernanos' case, there is no winning party to celebrate his prophet’s glory posthumously. Bernanos did not stand for any particular party: he stood against them all. He attacked, with equal measures of anger and lucidity, the Republic and the monarchy, communism and capitalism, the Revolution and the Old Regime, fascism and anti-fascism, Jews and anti-Semites, the clergy and atheists, the Masons and those who denounced Masonic conspiracies. Hence, no one was left to celebrate his victory.

The first to be defeated was the French right, to which he had served for so many years and whose demise he predicted – and desired – the moment it betrayed the nation, religion, and traditions by selling itself to the Prometheanism of the Darwinian and racist invader, the embodiment of what he called “the revolt of races against nations” (a revolt that, changing color, is still ongoing). A nation, he said, is a product of history and experience, a pact of friendship and collaboration laboriously erected among races, groups, and families. The race, a biological community without history, lifted its animal head to destroy, in a few decades, two thousand years of culture – the entire heritage that the right had claimed to defend.

But the betrayal was not only ideological; it was also strategic. For a decade, against the leftist hypocrisy that, following Stalin, sought accommodation with Hitler and the dismantling of the Army, the French right had called for rearmament, foreseeing war. After the invasion, the roles reversed: the right became collaborators, and the left, suddenly accommodating the USSR’s shift, managed to pass itself off as “early” resisters.

The left was also defeated, its hypocrisy constantly exposed by a succession of scandals and disasters, from the Khrushchev report to the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Democracy was defeated too, in its eagerness to rebuild the war-torn world, gradually using all the means of economic centralization and social control it had denounced in Nazi and Communist dictatorships, ultimately reaching the pinnacle of degradation by turning “human rights” into a tool of psychological oppression to dominate the frightened masses.

The Eastern European countries were defeated, escaping the Nazi wolf only to fall into the clutches of the Communist bear.

The Western powers were defeated as well, conceding half of Europe to the USSR, facilitating Soviet support for Chinese communism, the bloodiest tyranny of all time, resulting in the death of sixty million people – twenty million more than the total deaths of a war ostensibly fought to end tyrannies.

The Jews were defeated, in their rush to obtain material compensation for their suffering, exchanging their spiritual birthright for a police state hated by its neighbors and threatened by internal and external fanaticism.

The Catholic Church was also defeated, after aligning itself with parafascist corporatism, quickly shifting to overt support for atheistic progressivism, with the canine solicitude of one who, having lost its way, lavishes flattery on the first who gives it a lift to anywhere.

Last but not least, the people were defeated, no longer existing. Uprooted from their values and traditions, thrown into the whirlwind of a destiny they do not understand, dishonored and demoralized, having lost their identity, which was the fruit of history and the millennial practice of rituals, they have become an anonymous mass of loose atoms, with no other point of convergence than a TV screen from which they receive their daily dose of false fears, false revolts, false hopes, carefully calculated to abolish in them all sense of reality.

In the end, no one was left. Bernanos gathered everyone, communists and Christians, democrats and fascists, clergy and politicians, intellectuals and military, elite and people, under the general denomination of “les imbéciles,” certain that in the saving warnings he directed at them, they would be unable to see – with that infallible self-projective capacity of those who see nothing – anything but extravagant and purposeless anger.

Bernanos never had the illusion of being understood. But then, who was he speaking to? Curiously, this man, who on the surface of the world expected nothing but a callous stupidity consolidated by persistent sins, could glimpse, deep within each creature, a mysteriously preserved zone of all corruption, all lies, all self-deception. If Descartes said that all our mistakes come from the fact that before being adults, we were children, Bernanos thought exactly the opposite: the problem is precisely that we become adults and get contaminated with “l’incurable frivolité des gens sérieuses” (the incurable frivolity of serious people).

“I write,” he said, “only to be faithful to the boy I once was.” But that boy still remembered his childhood companions and recognized their faces, hidden beneath the anonymous mask of the crowd:

Companions, strangers, old brothers, one day we shall arrive together at the gates of God’s kingdom. Weary troop, exhausted troop, whitened by the dust of the roads, beloved hard faces whose sweat I failed to wipe, gazes that witnessed good and evil, fulfilled their duty, embraced life and death, O gazes that never surrendered! I shall find you again, old brothers. Just as my childhood dreamed you.

It was for these companions, still children and already immersed in the light of eternity, that he wrote. Thus, ultimately, they all understood him.

Among Catholic writers, none revered the Child Jesus more than Bernanos, the cult of invincible innocence. While Mauriac, Julien Green, and Graham Greene believed that Christian novels could only revolve around sin, with redemption merely hinted at from afar, Bernanos was the only writer, truly the only one in all universal literature, who managed to make holiness the very substance of the novel’s plot. His Diary of a Country Priest, which André Malraux and General de Gaulle considered the greatest novel in the French language, is an artistic tour de force in which, violating all apparent laws of fictional conflict, evil only appears on the periphery of the scene, with the center always occupied by sanctifying Grace.

Henri Montaigu, the great historian of spiritual France, who died prematurely, pointed out that, in the abysmal degradation of the Catholic clergy since the 18th century, the modern phenomenon of lay apostolate arises spontaneously, with figures like Léon Bloy and Georges Bernanos at the forefront. They retained something essential from the Christian legacy, which is no longer heard in what the spokesmen of the Catholic Church, both “officially” (let us say) and supposedly “dissident,” have to say. If you want to know what Catholicism is, forget the priests, the cardinals, the theologians. Read Bernanos.

Perhaps not by chance, the writer who throughout his life listened to the Holy Spirit had none of the external appearances of an ascetic. This voluminous man lived intensely and did not deprive himself of any bodily pleasures. He ate, drank, smoked, fought, made love. He even indulged, a motorcycle enthusiast before the Almighty, in the most modern pleasure of all, the thrill of speed, until breaking the same leg twice. However, he was genuinely an ascetic, perhaps the severest anchorite of the century, practicing the hardest discipline, inaccessible to many ascetics: he abstained from all the lies and collective illusions in which his contemporaries delighted, and to which many of us still beg for the morphine drop of false consolation.

He did not believe in socialism or fascism, democracy or technology, war or peace, the State or capital, promises of the future or a return to the past. He was never deceived by anything and even became, in contrast to almost all intellectuals of his time, a man of iron who did not need to cling to anything, who could live naked and devoid of all ideological protection.

Faced with the world’s folly, he did not even need the masochistic pride of the Stoic in the ruin of Rome, a ragged invalid clinging to the illusion of his own honor. Honor itself had become for him a dispensable luxury. For this reason, he could cast a more penetrating gaze on things than that of coldness: the fiery gaze of one who saw beyond the curtain of the world, in the perspective of the Final Judgment.

In his novels, every action is lived inseparably on two levels, brought together by the magic of words: the level of narrative time and that of eternity. Each decision, each glance, each gesture reveals its ultimate and definitive meaning in an instant: far beyond mere psychological unmasking, there rises the full metaphysical elucidation of everything that, for good or ill, has happened in this world. For this reason, his analyses of politics and history are so painfully true, as are his apocalyptic predictions that fifty years have continued to confirm. They blend into a single luminous ray the innocence of a child’s gaze and the complete, irrevocable disenchantment of one who has definitively given up believing in the world; of one who has become so realistic that he no longer needs even to cultivate the worst illusion of all, the one that remains at the bottom of the skeptical abyss, the illusion of realism:

I have always said that realism, far from being the perfection of politics, is, on the contrary, its negation. Lying and perjury are advantageous only in a world of honest people. But when the use of lies and perjury becomes general or even universal, the Machiavellis and the Tartuffes, all deprived of raw material, namely, the good faith of others, are reduced to the sad condition of unemployed.

Bernanos was, in a way, the symmetrical inversion of Chesterton’s atheist, who, “having ceased to believe in God, it is not that he does not believe in anything: he believes in everything.” Bernanos never needed to believe in anything because he believed in the one thing necessary.

November 25, 1998.

4. The Discreet Dynamiter

Maquiavel used to say that it’s better to be feared than loved. In this respect, Wilson Martins has nothing to complain about: I have never heard a word of sympathy regarding this critic, to whom his detractors do not spare, however, the respectful homage of their growls emitted from a prudent distance.

But what is so fearsome about this peaceful scholar? It is that he possesses the natural credibility of an honest critic, proven over four decades of rigorous literary exercise, and made immune to malicious attacks—that is, the only weapon left against someone who claims that two plus two equals four.

Martins, everyone proclaims, is a curmudgeon. Indeed, he is. He is an inconvenient man who dares to place Mr. Jô Soares and Mr. Chico Buarque hors de la littérature and refrains from providing many explanations, considering them too obvious. He stands out from the crowd mainly because he prefers literature more than its authors, and he judges them based on the services they render to it, with no concessions to the vanity of those who merely exploit it.

Such is he, that his curmudgeonly nature does not dull his literary insight and the rigor of his judgment. Some time ago, he wrote a dreadful article about Bruno Tolentino, making the worst insinuations against the poet, which are not worth recalling. In the last paragraph, he shifted the focus from the man to his work and admitted that it was “better than that of the best”: Cecília, Bandeira, Drummond.

It’s maddening. A Brazilian who, in the midst of anger, still has enough conscience scruples to seek fairness, and does so without any stinginess or malice, can only be a monster of coldness. Such a person stands in stark contrast to a country where the highest sanctity lies in sinning in the name of “emotion.”

To worsen things even further, Martins, perhaps because he lived in New York for so long, masters the typically Anglo-Saxon art of understatement. He sets a bomb under the bridge with the same indifferent face he puts sugar in his tea. One of his immortal footnotes in Estadão destroyed the false reputation of a pretentious intellectual without needing a single word. It was about a theorist of “process poem”—a school derived from concretism that, with absurdly precious arguments, ended up reducing poetry to a mixture of geometry and graphic art. I didn’t keep the entire footnote, but summarizing, it was something like this:

"Mr. So-and-so, in his theory, affirms that ↓ x ± © ◻.

The main argument he claims in favor of this is that ≡ √ ◊ ∑ ↔ .

Therefore, we can conclude that ↑ ⊥ * ¤ ∂".

Not always does Wilson Martins' aristocratically disdainful style reach such refinement. But restraining his opinion, allowing the facts to speak for themselves, is characteristic of his writings, in which, from time to time, the usually impartial and dispassionate tone becomes even more neutral and distant, transforming into a subtle irony that, for those who perceive it, is irresistibly comical. His masterful History of Brazilian Intelligence, which traces the mutations of the national spirit in its literary expressions almost year by year, is full of passages like these.

The adopted method is descriptive, taking both good and bad works, lofty ideas, and monumental follies as samples and symptoms of the mental state of our literary classes at each stage of History. Here and there, the author allows himself a very measured opinion, a judgment of value. But when he describes some sheer nonsense, some sample of the intellectual teratology with which our History is replete, all opinion is suspended, and the description, the colder it is, suffices to make the reader laugh… or cry. Balancing on a razor’s edge between a pity that does not wish to emphasize the ridiculous and a cynicism that emphasizes it by contrast, Wilson Martins' style, in these passages, is more than that of a great critic: it is that of an artist of words.

January 23, 1998.

5. Learning to Write

The act of learning to write – this is the very essence of a synthetic formula that contains many truths, but because it is so frequently repeated, it ends up having value in itself, like a fetish, emptied of those valuable contents that, to be grasped, would require the formula to be first denied and dialectically relativized rather than accepted without further thought.

To read, yes, but what to read? And is mere reading enough, or is something more required with what is read? When the formula replaces these two questions instead of eliciting them, it no longer holds any meaning.

The selection of readings presupposes many readings, and there would be no way out of this vicious circle without the distinction between two types: readings for mere inspection lead to the choice of a certain number of titles for careful and in-depth reading. It is this latter type that teaches how to write, but one cannot reach this stage without the former. The former, in turn, requires seeking and consulting.

Therefore, there is no serious reading without mastery of chronologies, bibliographies, encyclopedias, and general historical reviews. The person who has never read a book to the end but has, through searching indexes and archives, acquired a systemic vision of what to read in the following years, is already more educated than someone who, right off the bat, has immersed themselves in the Divine Comedy or Critique of Pure Reason without knowing where they came from or why they are reading them. But there is also what, if I’m not mistaken, Borges said: “To understand a single book, you must have read many books.”

The art of reading is a simultaneous operation on two planes, like in a portrait where the painter has to work on the details of the foreground and the lines of the background at the same time. The difference between a cultured and an uncultured reader is that the latter takes the current language of the media and vulgar conversations as the background, a one-dimensional frame of reference where everything subtle, profound, personal, and significant in a writer is lost. The former has more points of comparison because, knowing the tradition of the art of writing, they speak the language of writers, which is never “the language of everyone,” even though some good writers, mistaken about themselves, may think it is.

There is no such thing as a “language of everyone.” There are languages of regions, groups, families, and there are general codifications that formalize them synthetically. One of these codifications is the language of the media. It proceeds through statistical reduction and the establishment of standardized phrases that, through repetition, acquire automatic functionality.

Another, in opposition, is that of literary art. This one uses the richest and most meaningful expressions capable of conveying what could hardly be expressed without them.

The language of the media or the public square quickly and functionally repeats what everyone already knows. The language of writers makes sayable something that, without them, could hardly be perceived. The former delimits a collective horizon of perception within which everyone, by perceiving the same things in the same way and with minimal effort of attention, believes they perceive everything. The latter opens up, for attentive individuals, the knowledge of things that were perceived only by those who paid great attention before them.

It also establishes a community of perception, but it is not the community of the public square: it is the community of attentive men of all times and places – the community of those whom Schiller called “children of Jupiter.” This community does not physically gather like masses in a stadium, nor statistically like the community of consumers and voters. Its members communicate only through reflections sent, now and then, by the eyes of solitary souls that shine in the dark vastness, like the lights of farms and villages seen from the window of an airplane at night.