Modern philosophy has repositioned the logical problem, influenced by Kant’s criticism and Hegel’s dialectical contributions. Despite being overlooked and subject to derogatory criticism, Dialectics has made significant contributions to logical categories and science. This book explores Formal Logic, General Dialectics, and Decadialectics, adhering to certain norms. Formal Logic is briefly covered as its achievements are considered definitive, while new possibilities within the field, including phenomenological analysis, will be explored in “Philosophical Themes and Problems.” Dialectics, a growing discipline, requires answers to emerging questions. General Dialectics encompasses various important themes and necessitates investigations in other fields, acknowledging the influence of sensory, somatic, and affective aspects. Hegelian thought and dialectical perspective are relevant to philosophy, leading to the construction of a comprehensive worldview. This volume focuses on general aspects and introduces Decadialectics, aiming to coordinate existing dialectical structures. Other works will delve into specific dialectical topics. The methodology presented in this book enables comprehensive analyses while recognizing the partial role of formal logic. Dialectics is a logic of existence and becoming, encompassing oppositions without excluding formal logic.

- Preface

- Part 1 – “FORMAL LOGIC”

- Theme I

- Article 1 – Logic

- Article 2 – Thinking and Thought

- Article 3 – Logic and Psychology

- Article 4 – Thought and Thinking – Logical Principles

- Theme II

- Theme III

- Theme IV

- Theme V

- Part 2 – “DIALECTIC”

- Theme I

- Theme II

- Article 1 – History of Dialectic up to Plato

- Article 2 – From the Middle Ages to Nicholas of Cusa

- Article 3 – Kant, Fichte, and Schelling

- Theme III

- Article 1 – Hegel and Dialectic

- Article 2 – The Role of Logic in Hegel

- Article 3 – Problematics of Knowledge in Hegel

- Theme IV

- Theme V

- Part 3 – “DECADIALECTIC”

- Theme I

- Article 1 – Analysis of Phenomena – Their Interdependence – Their Antinomic Aspect – Movement, Mutation – Evolution of Phenomena – Antinomic Dualism

- Article 2 – Antinomic Dialectic of Quantity and Quality

- Article 3 – Reciprocity – Antinomic Dynamism of Extensity and Intensity – Contradiction in Unity – Theory of Dynamic Equilibrium – Categories

- Theme II

- Methodology of Decadialectic

- Theme III

- Article 1 – Contradiction in Decadialectic

- Article 2 – New Aspects of Contradiction

- Article 3 – Intrinsic and Extrinsic Principles

- Theme IV

Preface

One of the characteristics of modern philosophy is, undoubtedly, the new placement of the logical problem, especially after Kant’s criticism and the dialectical contributions of Hegel.

Despite continuing to be absent from official curricula, relegated to a secondary level, and suffering from the derogatory criticism of those who are unaware of it or who have a caricatured view of it, it is not possible, in the face of the impact of the themes on the value of logical categories, to continue ignoring the immense contribution of Dialectics, especially since it has penetrated the field of science.

In this book, where we study Formal Logic, General Dialectics, and our Decadialectics, we adhere to certain norms that we wish to draw attention to from the outset.

First and foremost, we do not extensively delve into Formal Logic because, in this field, what has already been accomplished is definitive. There is little to add here. That is the reason why we only address the most important aspects in a general manner.

It is true that logic now offers a new problem and theme, in which the studies of logistics and the contributions of many philosophical currents, such as phenomenological analysis, with Husserl at the forefront, offer new possibilities to invest in unexplored veins and make some unexpected revelations, even within the formal field. We will address these topics in the volumes entitled “Philosophical Themes and Problems” from the decadialectical perspective.

As for dialectics, we approach the general aspect based on the most well-known contributions. It is true that the dialectical theme and problem grow each day because, as a new and developing discipline, it faces numerous aspects that require answers to the constantly arising questions.

Throughout this book, the reader will notice that General Dialectics, which broadly encompasses such an important theme, requires the contribution of new investigations in other fields. These investigations stem from the dialectics of intellectuality in its operative polarizations of the rational and those of purely intellectual intuition. Since our process of reasoning cannot disregard the influence of schemes of sensibility, sensory-motor schemes, and also the somatic aspect that greatly influence our perspectives, and which modern psychology is highlighting, we must also acknowledge the functional inseparability of the affective part of our spirit. Its roots also extend into this somatic aspect, which, in turn, reveals the functioning of all sympathetic and antipathetic schematic constructions, the genesis of symbolism, which cannot be disregarded.

Furthermore, all those who have a keen interest in dialectical study sense the relevance of Hegelian thought, from which philosophy, in its general lines, can no longer distance itself. The dialectical perspective, being encompassing and inclusive, containing opposites, differences, and distinctions within itself, invades the field of philosophy and necessitates the construction of a general view of the world, a true world-view, which implies the need for a revision of all philosophical achievements. Thus, dialectics becomes philosophy, and philosophy, through its influence, becomes dialectics.

Now, such themes demand special works that coordinate what has already been constructed, albeit dispersedly, within a dialectical structure. In this volume, we focus on the general aspects, including a methodology that makes it practical, under the name of Decadialectics, a construction we have carried out with the intention of utilizing everything useful in this field for a more skillful handling by scholars of the subject.

However, topics related to noetic dialectics, as well as pathic dialectics, symbolic dialectics, and global and synthetic tensional dialectics, will be the subject of other works. Nevertheless, as the reader will see, the methodology presented in this volume is already sufficient for the undertaking of comprehensive analyses without disregarding the contribution of logic, which is always employed but with recognition of its role that, although important, is partial and consequently deficient in the appreciation of facts. Dialectics aims to be what it truly is: a logic of existence, a logic of becoming, and thus a logic that deals with dialectically considered oppositions without excluding formal logic.

MÁRIO FERREIRA DOS SANTOS

Part 1 – “FORMAL LOGIC”

Theme I

Article 1 – Logic

When man reached the rational phase, his thoughts began to process with a certain order, allowing him to draw conclusions, to direct them, transforming them into a powerful tool. From these observations, in a more advanced phase, he finally concluded that the regularity in his thoughts showed him that there was an order governing them. This realization enabled him to construct a science of thoughts by discovering relationships, rules, and constants.

This set of rules is called logic, which is the science of thoughts as thoughts, independent of other aspects and elements related to them, which form the objects of other sciences.

The study of logic is of indispensable necessity because it allows for the better application of thought, avoiding common errors. The reader is reading and contemplating these words and could mentally utter the phrase: “I am reading this book.” If we analyze the elements that compose or condition this sentence, we will observe, firstly, the reader who is thinking about this book; secondly, the act of thinking about the uttered phrase, which occurs in the reader’s mind; and thirdly, the thought itself, the simple assertion that “I am reading this book.”

The reader’s perception also involves the verbal statement of the phrase and, finally, the object to which the thought refers, as every thought is a thought of something. Let us call the reader the subject and the referred object the object, and we find ourselves facing the duality that is essential in the field of logic.

Thus: subject — perception or thought — object

Objects are classified in various ways by logicians:

We have sensible or real objects, which are those provided by sensory experience, whether through external perception or internal perception. Those of external perception are called physical objects, and those of internal perception are called psychic objects.

Physical objects are corporeal facts that occur in time and space.

Psychic objects are facts of consciousness. Desires, representations exist only in time, not in space, because they do not occupy a place, although they are related to a conscious being that possesses a body, such as man, as such, who occupies a place in space, as revealed by the concept of body.

Ideal objects are those that do not have a place in space or time, such as numbers, relations, concepts, as the concept of a book does not have a dimension or age. Thus, it cannot be said that the concept of a book has a meter or less than a meter, or a year or two years of age. This way of understanding ideal objects is the most common in philosophy.

We can conceptualize the idea of a book, but this concept is always conditioned by the books we know or imagine. There are reminiscences of our experiences in this concept that still offer certain limitations because if we cannot have the idea of a horse or the idea of a book determined in time and space, these ideas cannot surpass certain real conditions that we know through the exemplars that represent these objects individually. Thus, the concept of a horse cannot include something that would be a contradiction, like a horse that is not quadrupedal, etc.

Logicians also classify other species of objects, such as metaphysical objects and values. The former are known through reasoning or intellectual or pathic intuition, as will be seen in “Ontology and Cosmology.” As for values, they are “qualities” of a special order, the study of which belongs to Axiology (the Science of values), and we study them in “Concrete Philosophy of Values.”

Article 2 – Thinking and Thought

The subject of thinking is the one who thinks, a real and temporal subject. It is the human mind that carries out the act of thinking (thinking, measuring, calculating). The act of thinking is always new as an act. So I think about the book in front of me, and every time I engage in this thinking, I perform a new act. I think about the book today, and I will think about it tomorrow as well. The act of thinking is different, but the thought book remains the same. This happens because what we conceptualize, we extract, abstract from things.

This concept remains virtualized in our mind because the concept of a book is not a real object but rather what we generalize from the book, an abstract schema. We call any object that, in actuality, that is, as an object, happens here and now, corresponding to that ideal book that we virtualize, a book. The concept remains in my mind as something virtual, which is not yet existentially in act.

The virtual being (which philosophers usually call being-in-potential, that is, a being that is not yet but can potentially become actual) is not being in time or space, as it does not occupy a place or change with time.

The book, as an act (this book, that book), “occupies a place in time and space.” Therefore, when we think about the concept of a book three times, we perform three mental operations of thinking, in other words, we think three times, but the concept of a book remains the same in all of them because we separate the concept from time and space, while in thinking, we are time and space, and thought is something we repeat because it is not time or space.

Thus, when we think about the triangle three times, we perform the act of thinking three times; however, we do not have three triangles but only one because the concept of a triangle is something we separate from time and space. The triangle that is here can be larger or smaller in actuality, even though, as a concept, it does not have dimensions or specific angle measurements other than the sum of two right angles, which is mathematically necessary for the conception of a triangle.

However, we all feel it when we say, “I had the same thought as you,” that is, when someone else’s thought coincides with ours. Thus, we see that we perceive the reality of one of the most important points in logic, which is the distinction between thinking and thought. The former is the object of psychology, and the latter, of logic.

Every thought corresponds to an object or objective situation to which it tends, directs itself, which is why thought is said to be intentional.

Intentional, because it has intention (from intendere). This expression comes from scholasticism but is currently used again in the sense of the application of the mind to an object of knowledge, the act that tends toward the object and also as the content, the object itself, to which the mind applies itself. Every thought is an application to an object; therefore, it is intentional because every thought is a thought of something.

Logic studies thoughts as thoughts, and when it empties them of their contents and studies them as generalities, observing them as forms, it is called formal logic.

Observation shows us that every science has its own logic. General or formal logic seeks to synthesize them into a universal, general basis. Let’s consider enlightening examples. If we consider the concept of Man, we will find that in anthropology, physiology, and anatomy, it has a content, particularities different from Man when used in philosophy or sociology. Each science gives concepts characteristics that are peculiar to it. Formal logic studies thoughts, concepts, etc., as forms (as “forms,” we could say, that is, emptied of their contents) and studies them independently of their peculiarities. That’s why it is called formal logic.

Logic is the science of thoughts, and formal logic is the science of thoughts as forms, in other words, just as thoughts, emptied of their factual content.

Both logicians and philosophers discuss whether logic is a theoretical science or a normative science or just an art or technique. Naturally, we won’t reproduce those lengthy discussions here, but we could say that each side has a valid point because logic can be regarded, employed, and studied from any of these aspects.

It is a theoretical science when it speculates about the elements that form its framework; it is normative when it offers rules by which we can assess whether a thought is right or wrong. Thus, it addresses all these aspects, which does not prevent those who are eager to delve into theoretical logic alone from doing so, while others study only its normative application. The great surge currently taking place in logistics, mathematical logic, and various dialectical formulations demonstrates the great possibilities of making it eminently practical and useful without denying the efforts of those who aim to study it solely as a theoretical science.

Article 3 – Logic and Psychology

It is very common to find, among logicians, including philosophers of the past and present centuries, the concern to reduce logic to psychology, that is, to consider thoughts as mere psychic data. This tendency is called psychologism, just as the tendency to reduce psychic phenomena to biology is called biologism, and the tendency to reduce the biological entirely to matter is called materialism. Logical psychologism defends the opinion that logic is based on psychology or is dependent on it.

Logicians who do not accept this opinion argue as follows: logical objects are not empirical objects but ideal ones, as we have already seen.

Secondly, the laws of logic are universal laws constructed a priori, and not inductive generalizations, that is, constructed from the observation of particular facts to reach the general. Thus, inductive laws are generalizations that have a high degree of probability but can never be asserted as absolutely certain, while the laws of logic offer evidence that nothing can destroy. Inductive laws are formulated a posteriori, that is, after the observation of particular facts to reach a generalization. They are therefore based on temporality since they are laws of an occurrence in time, while the laws of logic, like those of mathematics, do not depend on time.

As seen, the reasons are considerable, but on the other hand, we must also consider those offered by those who defend the reduction of logic to psychology. For example, they claim that logical data are perfectly explainable by psychology, and if they seem to occur outside of time, it is only the result of an abstraction that leads to placing thoughts outside of time. Currently, this is a pronounced tendency among modern logicians.

History of Logic – It was the Greeks who made logic an autonomous science, and among them, Aristotle, who studied it in his Organon and presented important investigations. However, Aristotle never considered logic merely formal, as a study of thoughts as thoughts, but rather as a kind of methodological introduction to philosophy.

In the Middle Ages, Aristotle’s work was continued, although sporadic voices arose against such an orientation, advocating for a more practical and experimental approach. Only in the so-called Modern Age, with Galileo (1564-1642) and Bacon (1561-1626), did logic employ consistent methods in combining experience and mathematics, as Leonardo da Vinci had already proposed. Bacon considered logic as a doctrine of knowledge through experience and facts to reach natural laws, strengthening the inductive method, which he studied extensively. John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) continued Bacon’s work and added some new rules to those presented by him. These two aspects of logic, the theoretical and the practical, have been debated since then until the present day.

Article 4 – Thought and Thinking – Logical Principles

Regarding thought, we still wish to make some considerations that we deem of utmost importance for the future understanding of logic and the disputes between psychologism and logical formalism. Philosophically, thought is considered in two senses: in an extensive sense and in a restricted sense.

In the first sense (extensive), thought encompasses all phenomena of the mind. Thus, thought is everything that possesses a character of rationality and intelligibility, even without actual consciousness. Some assert that nature, and even being as a whole, is a thought. Let us provide an example: in every fact, in universal occurrences, in objects, in psychic acts, in anything, all possible thoughts are already present. In the face of any event, we can grasp different or similar thoughts, as we have seen before. Thought, in this way, is not a product of our mind. Our mind merely apprehends, captures thought. Therefore, everything is thought, everything is, in essence, logic. Hence the tendency called panlogism (from the Greek word “pan,” meaning everything). This is one of the arguments that underlie theoretical logic against psychologism. Thus, our mind only plays the role of a receptor, apprehender, capturer, not producing or elaborating thought, but merely catching it. Thought, in this manner, permeates all of reality.

In the restricted sense, for some, thoughts are all cognitive phenomena (in opposition to feelings and volitions, which we will study in “Psychology”). Thus, thought is synonymous with intelligence, in the sense of the set of all functions that have knowledge as their object, in the sense of sensation, association, memory, imagination, understanding, reason, consciousness.

More narrowly, thought is understood only as synonymous with intelligence, but only concerning understanding and reason, as they allow for the comprehension of what constitutes the subject matter of knowledge, without being confused with perception, memory, and imagination.

Thus, thought, in the extensive sense, is distinct from the psychic act (act of thinking), as the latter occurs anew in each person, while the former can be grasped by different people without ceasing to be the same thought.

However, we could add that without psychological functions, the operation of capturing thought would be impossible. This argument will be important, especially when we study its virtual aspect, that is, thought not as an act, but as the virtualization of experience, after all factual aspects have been removed, when it becomes pure abstraction.

This operation of abstraction is possible and repeatable in everyone, although the product is the same.1

In every act of thinking, there is the apprehension of a thought; thinking thinks a thought.

In the act of thinking, there is a unity between thinking and thought, without reduction, without one being confused with the other, as logicians emphasize.

Thinking is a temporal, empirical, and psychic act, while thought is timeless.

The laws of thinking are studied in Psychology, while those of thought are studied in Logic. It is important to highlight this distinction between thinking and thought because, in dialectics, we will have the opportunity to analyze this aspect of our understanding. Thus, the functioning of the act of thinking falls under the study and analysis of Psychology.

As for thought, Logic, which is its science, studies and establishes its laws. However, Psychology is inseparable from Logic because, in the face of thinking thoughts, it studies the order and legality (the character of being governed by laws) that govern them and establishes their connections.

In Philosophy, there is a discipline, the science of “being as being,” which is Ontology. In this traditional sense, Ontology is the science that deals with being as being, that is, the being that constitutes everything that exists, the being that determines all beings. There are other ways to conceive them that it is not appropriate to discuss at this time. In this discipline, the “ontological principles” are studied, which apply to all objects, to which all others are subject, including logical objects. They are as follows:

- Every object is identical to itself — This is the statement of the so-called ontological principle of identity.

This fundamental principle of classical Ontology is also true for Formal Logic. For now, we only need to present it as a true axiomatic foundation of Ontology and consequently of Formal Logic. Thus, it can be exemplified as follows: this book is this book; this table is this table.

For traditional Ontology and Formal Logic, this book, formally, can only be itself; it is identical to itself. From this fundamental principle, other consequences follow, which are generally given as ontological and therefore also logical principles:

- No object can be both itself and not itself.

Ontological principle of non-contradiction. It is stated by saying that A cannot be both A and not-A under the same aspect.

- Every object must be A or not A.

That is: This object is a book or it is not a book.

Ontological principle of the excluded middle, as it excludes an intermediary between being and non-being.

The ontological principle of identity becomes in logic the “logical principle of identity”. It is true when we affirm that this book is identical to this book, that is, A is A.

The applications of this principle in Logic require a more detailed explanation and are studied in the part that deals with judgment, with practical applications and their systematization.

The “logical principle of non-contradiction”:

This principle follows from the first one. If we affirm, “what is, is; what is not, is not”, or in other words, “this book is a book”, and at the same time “this book is not a book”, one contradicts the other because in the first statement, we affirm that the book was a book and then the opposite, thereby denying the truth of the first principle.

And since we accept that the opposite of the true is necessarily false, we cannot simultaneously assert that something “is and is not”. The statement “the opposite of the true is false” is the enunciation of this second principle, also presented by the formula: “No object can be both itself and not itself”.

The “principle of the excluded middle”.

Now, if by the principle of non-contradiction, according to formal logic, we conclude that two contradictory statements cannot both be true, by the principle of the excluded middle, we conclude that if one is true, the other is necessarily false, although this principle does not decide which one is true and which one is false.

Thus, if we say, “Every man is mortal” and “Some man is not mortal”, one is true and the other false; a third position is excluded, that is, it is not possible to admit that a man is mortal and not mortal when he is mortal.

Therefore, it is called the principle of the excluded middle because it excludes a third positivity among those.

This same principle leads us to understand that when two statements contradict each other, they cannot both be false.

If we recognize the falsehood of one, we can affirm that the other is true, and vice versa. If one of the judgments is true, the other is necessarily false; a third position is excluded.

Principle of sufficient reason.

This principle is also considered one of the logical principles. It could be stated as follows: a statement is true or false; if it claims to be true, it needs a reason that supports it. This reason is called “sufficient” when it is enough to provide complete support.

It is a sufficient reason when nothing else is needed for the statement to be true.

Another principle also considered among the logical principles is the “Principle of the syllogism”, which can be stated as follows:

“If a implies b and if b implies c, a implies c”.

Implication (entailment), in the formal logical sense, is a relationship that asserts that one statement necessarily results from another.

Thus, the “idea of a mammal implies the idea of a vertebrate”, “the law of gravitation implies the law of the fall of bodies”.

Theme II

Article 1 – The Concept

For Formal Logic, the concept is an ideal, timeless object of thought: in short, it is the object of Logic. The concept, as a psychological operation, both in its genesis and in its action, belongs to the study of Psychology.

It is worth noting that while the concept in Formal Logic presents itself as a universal structure, isolated from time and space, detached and liberated from individual contingencies, the psychological operation varies from one individual to another, and within the individual, according to the variations they experience throughout life.

This distinction is important and becomes clear when we closely examine the difference between acts and contents in the concept. Acts are functions of consciousness, real, effective, temporal psychic processes. They are distinguished from the contents, which are independent of consciousness, ideal, timeless, and autonomous.

Logic studies these contents, while Psychology focuses on the study of acts. However, since both are correlated, since both condition each other, Psychology cannot do without the contents for greater assurance in its study.

This antinomic dualistic aspect of the concept, which arises in relation to Psychology and Logic, explains why when we pronounce the verbal statement of a concept, for example, book, there is something that occurs in the minds of those who hear it that is the same for everyone: the meaning, the concept. However, many other distinct elements, a series of psychic processes, accompany the effort of understanding that each individual performs. Within the same individual, from the suspicion of the concept’s content to its full comprehension, a process takes place.

The concept is the element on which logic relies. And the fundamental logical structure is judgment, which we will now study.

Judgment, in the broadest sense, is the act of positing the existence of a specific relation between two or more terms. As the scholastics used to say, it is the intellectual act by which we deny or affirm one thing of another, or in which we attribute a predicate to a subject, for example: “The book is green.” I attribute the quality of green to the book. Book is the subject of the judgment, green is the predicate. As for the element “is,” which is the relating element, we call it the “copula.” A judgment can have a multiple subject and a multiple predicate. For example: “This book and those ones are green and big.”

The concept follows a path of constant abstraction to the point where, in the logical-formal sense, it already sheds those characteristic notes of the object whose repetition allowed the mind to construct the common denomination of the concept.

If we take the example of the concept house, we will verify that it no longer reproduces the essential notes of the corresponding object.

For formal logic, the concept house is distinct from the object house. It is not difficult to understand the reason. If we ask a child what a house is, they will immediately have various images of the houses they know or have known. And if they try to define it, they will say, “Well, it’s where people live.” Finally, after showing that people also live in other places that are not houses, the child will say that they are covered places where we have the possibility of inhabiting.

In the end, they will give a delimited content to the concept of a house. But this concept, although referring to an object, because every concept refers to objects, in the cultured development of humanity, it takes on more and more its own formal significance. The concept stands out from the object itself in constant abstraction, to the point that when we speak of a thing, or think of a house, its jactic content is being replaced by an increasingly vague, separate, and abstracted eiaetic content, detached from the images associated with the material content of the concept, to form a logical entity. The need for simplification that the cultured man has in his relations with his fellow human beings, the continued, almost sick and addictive reading, the constant word he hears, the meditation and various thoughts that suggest a life in constant motion, all this would not allow the material content to be linked to each concept. We read pages and pages of books, experiencing the words without having to associate more or less precise images with each one when they represent concepts. Otherwise, we could not keep up with the rapid pace of our existence. This is why the concept becomes a logical entity, increasingly stripped of its material content, and when modern logicians believe they have discovered the true character of the concept, they are only verifying what is characteristic of our degree of culture and civilization, in contrast, however, to other pre-cultured eras, because even for logic, there is a historical conditioning.1

This also leads us to make the distinction between the concept and the image. It is said, for example, that the concept is a attenuated, more indecisive image. Now, the image is always individual and concrete, composed of sensible data. The image I have of a book is of this or that book, retaining the appearance and size of a book.

But the concept is general, and the concept of a book, with which I think about a book of any kind or size, has nothing singular about it. However, since I do not want to memorize just the image of a specific book, in every image that presents itself to my memory, which I “visualize,” I find that other images penetrate it, that it merges with others of similar objects, or is replaced by the image of another object.

So when I want to visualize the concept of a book, I can have the image of this book in mind, but other images penetrate it, or one is replaced by the image of another book.

It is natural that the armchair logician, accustomed to constant work with isolated concepts devoid of any material content, wants to give maximum value to what he calls pure intellection or eidetic intuition.

The same happens with these individual, singular concepts as well. Let’s take, for example, “Napoleon Bonaparte.” Napoleon Bonaparte was unique and will not be repeated as a singularity in history. However, we use him as a concept. But who could deny that we have a certain number of notes about Napoleon Bonaparte that individualize him, that form a kind of blurry image of what we know about him through what we have read, seen? We can use the concept Napoleon Bonaparte as a purely logical entity, stripped of its material content, when we read or when we speak or think. But that only indicates the capacity of our mind for increasing abstraction, abstraction that comes from simple perception, through the memorized image, to the concept with the material content, and from there to the concept of pure intellection and eidetic intuition, which modern logicians talk about so much.

The objective content of a concept is the set of these mental references, these notes of the object. However, the concept does not adhere to all the known notes of an object. There is a selection of notes; we find this selection in every vital phenomenon, which led Bergson to say these words: “… every living being, perhaps even every organ, every tissue of a living body… knows how to gather from the environment in which it exists, from substances or from the most diverse objects, the parts or elements that could satisfy one or another of its needs; it neglects the rest. Therefore, it isolates the character that interests it, goes directly to a common property. In other words, it classifies, and therefore, it abstracts…” (La Pensée et le Mouvant, p. 66).

This selection occurs by neglecting certain notes and by embracing others. The concept, therefore, cuts out from the object what interests it and sticks to that. This portion is what is called the formal object.

We see that the object is always connected to the concept. Some argue against this, citing certain concepts of fiction, such as myths (the centaur) or fictional characters like “Madame Bovary.” However, there is objectivity in these concepts because either they exist and move within the pages of literature or they are creations of the mind, which have objective contours, always extracted from human experience. The individual concept also leads us to form an opinion that we believe deserves examination. The individual concept is not the same as conceptualization, as we explained in Philosophy and Worldview. The long exercise of conceptualization allowed us to conceptualize, subsequently, even the individual. As we have had the opportunity to say, we will call concepts the common denomination we give to a series of similar facts that appear identical to us.

Initially, every concept is a denomination of something general. However, when we speak of concepts like Napoleon Bonaparte, America, the Sun, and others, it is necessary to observe that this work of conceptualization, of abstraction of individual notes, to become a logical entity, only takes shape later in humans, after the abstracting work of concepts has had extensive practice. Regardless of the limited number of logicians, there are a great many human beings who do not easily conceptualize the individual, which proves that a certain mastery in one function is not enough to justify such great leaps. In other words, the logician cannot conclude that there is a concept of the individual. The concept is general. The conceptualization of the individual is based on universal experience or on various notes, some similar and others different, formed from a particular singularity.

Let’s exemplify: America. Despite referring to a continent, which is unique in our world, an individual, therefore, it contains immense possibilities within that simple word: America is also the new continent, the land of great hopes, its history, its indigenous inhabitants, its functions in the historical events of humanity, habitat, and a place where diverse populations from many parts of the world live. America is thus a set of notes that allows for conceptualization. Let’s see another example: “Napoleon Bonaparte”: he is not just the man, the politician; he is the military, the revolutionary, the consul, the emperor, the Napoleon of Arcola, the Napoleon of the Russian campaign, the Napoleon of Saint Helena, etc. In short, a collection of notes that offer different perspectives to those who think about him. As for the concept Napoleon Bonaparte, it is the common denomination for this series of facts connected to an individuality that gives it a common name. This is how the concept Socrates is, and Plato, etc.

In the classification of concepts, we will provide here only the most general ones: specific concept refers to what corresponds to a species; generic concept refers to what corresponds to a genus; general concept (also universal) indicates specific or generic concepts, such as “color,” “animal,” etc.

Concrete and abstract concepts. The former refers to objects that are intuitively representable, such as “house,” “book”; the latter refers to those that are not, such as “passion,” etc.

Collective concepts express a homogeneous and unitary set of objects, such as “crowd,” “mass,” etc.

Content, extension, and comprehension of concepts — Every concept has content, which is given by the fact that it refers to an object, and it consists of the references it exposes. The content of a concept is its comprehension; it is the selected notes of the object.

Extension is the generality, the number of objects encompassed by the concept. The greater the generality, the larger the extension of the concept, and the smaller its comprehension, which is the number of qualities it encompasses. For example, the concept “animal” has a larger extension than “man” because it has greater generality, including all animal beings classified by zoology, including humans. However, the notes we select for this concept are fewer than those for the concept man, which, nevertheless, has a smaller extension but greater comprehension, because when we consider “animal” as a zoological generality, we have already excluded the rational note that belongs to humans. When forming the concept of “animal,” the number of notes is smaller; that is, the number of notes we can assign is smaller.

Thus, by increasing content, extension decreases. For example, “white man” is a concept with smaller extension than “man,” but it has greater comprehension, greater content.

Content can increase or decrease. We could add previously ignored notes or disregard others that were previously accepted, which are virtualized as non-existent.

Extension can be considered in an empirical sense, depending on all the objects falling under the concept, or in a logical sense, leaving aside concrete individuality, empirical individuals that arise or disappear, and focusing only on logical objects.

Singular concepts have no extension, such as Napoleon Bonaparte. It is the content that determines the extension. The more general the concept, the smaller the content and the greater the extension, as we have seen.

Concepts relate to each other. Therefore, there is a subordination of some to others. In this case, the subordinate concept has all the constitutive references of the dominant concept, plus some of its own. The actual content of the dominant concept is smaller than that of the subordinate concept. Polygon is the dominant concept of triangle, but the latter, in addition to the notes of a polygon, has the note of having three sides.

Coordination relation exists between two or several concepts that are in the same order, in the same classification; these are, in particular, in a classification by generality, two species of the same genus.

Dependent concepts are those whose objects have dependence among themselves. Example: father and son; cause and effect. They are also called correlatives.

Disjunctive concepts fall under the same superior concept but do not have any sector of their own extension in common. Coordinated concepts are also disjunctive; for example, species of a genus.

Contradictory concepts: those that negate each other’s content. For example: white and non-white.

Antagonistic concepts: those whose opposition is polar, for example: good and evil.

These are the most common classifications found in Formal Logic.

When a concept lacks meaning, it is said to be meaningless. For example: hat but satisfied.

Absurdity occurs when we think of contradictory notes in a concept. Absurdity can be logical or ontological.

Logical: for example, a round square. The contradiction is evident within the concept itself.

Ontological: when the incompatibility is verified by the object itself. For example, “a centimeter of love.” Although it does not contradict the laws of logic, it contradicts the laws of the object, as love, being an affection, does not have extension.

Functional concepts are those whose performance consists of relating concepts. For example: The book and the table are in the room. And, are, and not are functional concepts because they relate the concepts table and book.

Article 2 – Judgment

The study of judgment, from a psychological point of view, belongs to Psychology, where the operation of judging is examined, as well as the factors that influence it, in addition to its modalities. Here we are only interested in its logical aspect, that is, as an ideal object.

We can take advantage of a classical definition that says: Judgment is the intellectual act by which we deny or affirm one thing of another. When we affirm, the judgment is affirmative; when we deny, negative. For example, “The Earth is round,” that’s the first case; “the Earth does not have its own light,” that’s the second.

Judgment is expressed through words and is also called proposition.

Thus, the internal act by which I affirm that the Earth is round is a judgment; the words I use for that affirmation form the proposition. We can now distinguish the concept of judgment: the concept is of a presentative nature, while judgment is enunciative.

Reasoning is an ordering of judgments, a discursive operation by which it is shown that one or several propositions (called premises) imply another proposition (conclusion), or at least make it plausible. Judgment is not only a connection of concepts, as it is an act of thinking that can be considered true or false. In it, the taking of a position, the assertion (positive or negative), is essential. When I say, “neither this nor that table,” I make connections of concepts, but I do not elaborate a judgment because I do not assert anything.

In every judgment, there is a relation between one thing and another: what is affirmed or denied, and that of which it is affirmed or denied. It is the subject-concept, the object upon which the enunciation, the affirmative or negative assertion, falls. It is called predicate-concept or attribute, which is affirmed or denied, negatively or affirmatively, with regard to that subject-concept. Without this assertion, there is no judgment, because, as we have already seen, judgment is not only a connection of concepts.

A third element enters into the judgment, which is the expression of the relation between the predicate-concept and the subject-concept, which is the copula, which has the function of attributing the predicate to the subject, that is, of making the assertion. The verb to be is commonly used as a copula, for example: Love is a feeling. Love is the subject; feeling is the predicate or attribute; is is the copula.

In propositions where the verb to be is not expressed, it is understood.

According to the objects, judgments can be classified as:

Real or empirical judgments (also called judgments of existence) are those that deal with empirical facts, whose starting point is always a sensory experience. Example: This book is green.

Judgments of ideality or ideals are those whose object and predication are ideals. Examples: “The part is smaller than the whole,” etc. “7 plus 3 equals 10,” “two things equal to a third are equal to each other.”

Metaphysical judgments: those that deal with metaphysical objects.

For example: “the being of man is rationality.”

Pure value judgments: those that state something about values or their relationships: “Moral value is worth more than utilitarian value.”

Determinative judgments are those that state the essence of the subject-concept and answer the question what is this? For example: The lion is an animal.

Attributive judgments answer the question how is that?

For example: This book is red.

Judgments of being are those in which the predicate states the objective category to which the subject-concept belongs, for example: This book is a paper artifact.

Predication can be:

a) Comparative, when the subject-concept is compared with another, for example: France is larger than Belgium;

b) Possessive, when a relationship of ownership is affirmed or denied between the subject-concept and others, for example: This book is mine;

c) Dependence, when it is affirmed that the subject-concept depends in any way on another, for example: “Heavy rains cause rivers to overflow”;

d) Intentional, when the subject-concept receives an intention from another object. For example: The establishment of justice is the purpose of righteous people."

When studying the categories in Philosophy and Worldview, we saw that Kant divided them into four classes: quantity, quality, relation, and modality.

Every judgment can be considered from four points of view, which is important in the study of Logic.

Let’s see: According to quality, judgments are affirmative or negative, as we have already shown.

Regarding quantity, they are universal when the subject-concept contains the main concept in its entirety in plurality. For example: All Brazilians are Americans; particular when the main concept is taken in partial plurality, for example: Some men are Bahian.

The quality and quantity of judgment vary independently and allow for four classes of judgment that are important for the theory of reasoning. They are indicated by these four vowels: A, E, I, O.

Universal affirmative judgments (A): all S are P. Example: All Brazilians are Americans.

Universal negative judgments (E): no S is P. Example: No Brazilian is European.

Particular affirmative judgments (I): some S are P. For example: Some Brazilians are Bahian.

Particular negative judgments (O): some S are not P. For example: Some men are not Brazilian.

Regarding relation, judgments are divided into categorical, hypothetical, and disjunctive.

Categorical when the enunciation is not conditioned; it is independent. For example: “Today is Sunday.”

- The categorical judgment is subdivided into problematic, assertoric, and apodictic.

a) Problematic: when the proposition can be true, but the one who employs it does not expressly affirm it. Example:

“The world is the result of chance or an external and necessary cause.”

b) Assertoric: they are true in fact but not necessary. Example: “The moon is a planet.”

c) Apodictic: when the judgment is necessarily true, such as mathematical truths. “The whole is quantitatively greater than its part.”

Hypothetical Judgment. Judgments are hypothetical or conditional when an affirmation or negation is subordinate to some condition or hypothesis. For example: “If the weather is good, I will go to the cinema.”

Disjunctive Judgment. Judgments or propositions are disjunctive when they consist of two relationships, each of which is affirmed only when the other is denied. It is equivalent, in reality, to two hypothetical judgments. For example: “If John is not wise, he is ignorant.” “If John is not ignorant, he is wise.”

These two propositions must be proven separately. Together, they form an alternative.

If A is not C, it is B. If A is not B, it is C.

Regarding modality, judgments are assertoric (it is certain that…), problematic (it is possible that…), or apodictic (it is necessary that…).

Also called impersonal judgments are those that apparently lack a subject-concept. For example: It’s raining.

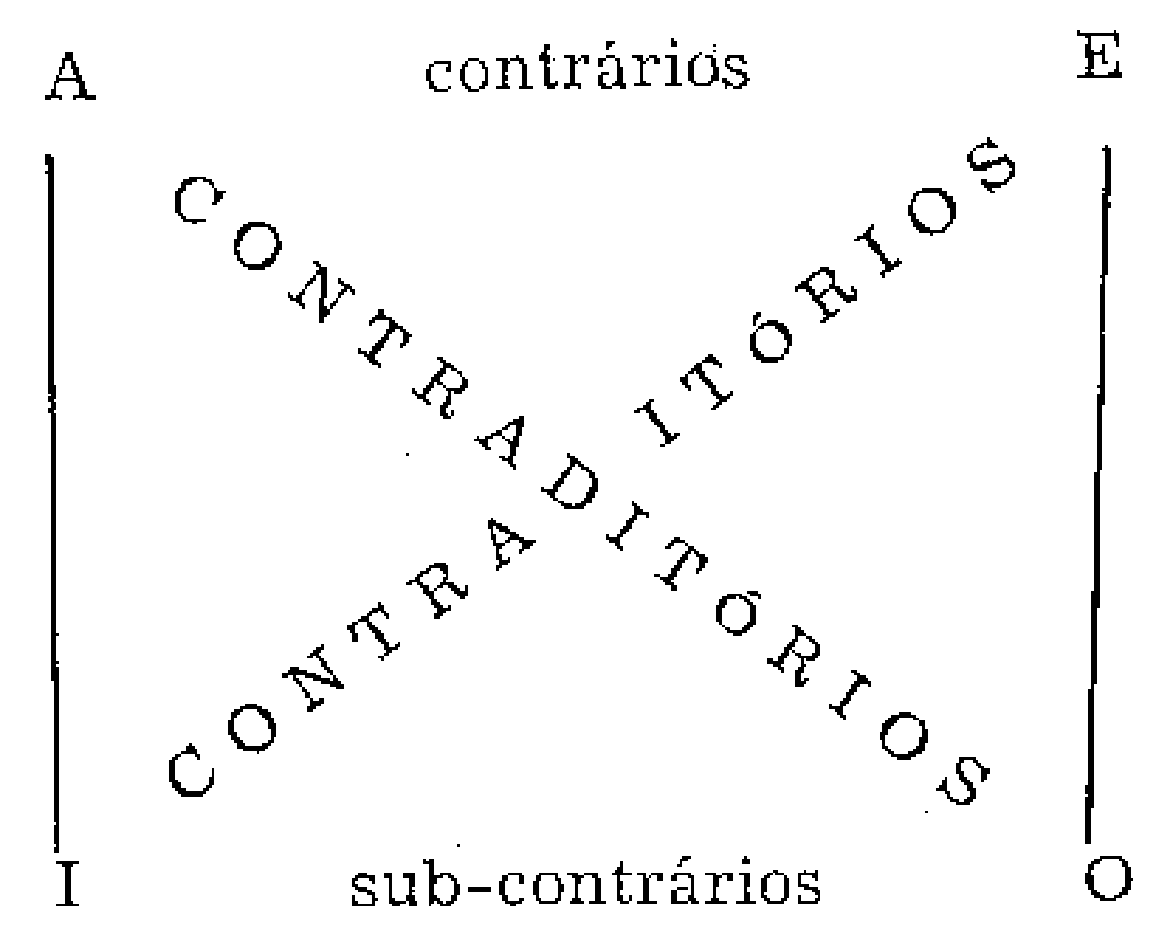

Relations between judgments. Contradictory judgments are those that, referring to the same situation, one affirms and the other denies. Contradictory judgments are the affirmative universal (A) and the negative particular (O); and the negative universal (E) and the affirmative particular (I), whose contradictory relationship is reciprocal. “Every S is P” is contradictory to “Some S are not P,” and vice versa.

For example: “every Bahian is Brazilian” (A) – “some Bahians are not Brazilian” (O); “no metal is a metalloid” (E) – “some metals are metalloids” (I).

Contrary judgments are those that, both being universal, one affirms what the other denies. Contraries are the affirmative universal (A) and the negative universal (E). Contrariety is reciprocal. Examples: “every Bahian is Brazilian” (A) – “no Bahian is Brazilian” (E).

Subcontrary judgments are those that, both being particular, one affirms what the other denies, and the relationship is also reciprocal. “Some S are P” is subcontrary to “Some S are not P.” Examples: “Some Americans are Brazilian” (I) – “some Americans are not Brazilian” (O).

Subaltern judgments are those that have the same subject and the same attribute but differ in quantity, not quality. The universal is the subalternating to the particular, which in turn is subordinated to the universal. “Every S is P” subordinates to “Some S are P,” and “No S is P” subordinates to “Some S are not P.” Examples: “Every Brazilian is American” (A) – “Some Brazilians are American” (I); “No Brazilian is European” (E) – “Some Brazilians are not European” (O).

Here is the traditional scheme:

Theme III

Article 1 – Definition

We can emphasize that the definition answers the question “what is this?” but offers a response with a sense of determination, of maximum determination. The definition aims to answer that question, not with just any clarifying response, but with the response that determines, that completes, that is an equality, the precise delimitation of the defining, that is, what is to be defined, a sufficient response for us to know what that is about which the question was formulated.

Now that we have studied what a judgment is, we can say that a definition is a judgment, as it states an affirmation about the being of the object, delimits it, says what it is, and at the same time separates it from what it is not.

Philosophers usually classify definitions as nominal, real, formal, and material. These are not the only classifications, as there are others. Let’s analyze them:

The nominal definition is also called verbal, and it consists of explaining the meaning of a word using another or other words with a known meaning. Nominal or verbal definitions are the ones most commonly used in dictionaries. Many consider these verbal definitions as tautologies, that is, repetitions. Although they are often considered tautologies, which they seem to be from a purely formal point of view, there is, however, an experiential layer in the definition that clarifies what is to be defined. Since this aspect already enters the field of Psychology, we will study it there. The definition refers to one, several, or all the notes of the object referred to by the concept, whose content is revealed to us. The real definition is the definition of the thing, a determinative formula that expresses what the thing the word signifies is.

Kant called the former synthetic definitions (nominal and conceptual definitions), and the latter analytic definitions.

Many philosophers distinguish real definitions from conceptual definitions, giving conceptual definitions a preference for the formal object, which is part of the total object. Many consider nominal definitions to be identical to formal ones and real definitions to be identical to material ones. However, the formal definition is properly a conceptual definition.

These divisions are arbitrary, and for that reason, some philosophers offer other ones. Thus, they propose the genetic definition, which defines the object by exposing its formation, its genus. For example, we want to define a circle and we say “a circle is the figure described by a line segment rotating around one of its endpoints.” Although such definitions are widely used in mathematics, like the one that says “a line is the result of a point moving in space,” many philosophers consider them unacceptable. However, as Hamilton, Krug, and Blondel point out, these definitions consider the defining in its progress or becoming, for, as Blondel says, it is the fieri (becoming) that clarifies the esse (being)."

To be rigorous, a definition is constructed with the help of the nearest genus and the specific difference. The former indicates the nearest genus to which the object to be defined belongs (for example, “a pentagon is a polygon”). The latter sets the pentagon apart from all other polygons (for example, “it is a figure with five sides”). The final statement will be: The pentagon is a polygon with five sides. Thus, for example, man is a rational animal. Animal is the nearest genus; rational is the specific difference that distinguishes man from other living beings.

Explanation should not be confused with definition. Explanation states something beyond the definition in order to clarify, showing properties, characteristics.

When we say that man is bipedal, lives in society, makes choices, appreciates values, cares, has an understanding of his possibilities, knows death, creates various ways of living, all of that would be explanatory, clarifying, not a definition.

There are some definitions that are called negative. They are characterized by negating some determination to the defining. For example, when we say, “immortal is that which does not perish.” In reality, the negativity of these definitions is only apparent, as it assumes the positive determination of the corresponding positive concept.

An essential definition is one that is stated by indicating the characteristics without which the defining would cease to be what it is.

An accidental definition sticks to an accidental determination, for example, when we say, “Peter is the person sitting next to the door.”

If we affirm that a definition, to be rigorous, must follow the classical rule, being constructed with the help of the nearest genus and the specific difference, we conclude that the ultimate genus is indefinable because it cannot be referred to another. This happens when we go from genus to genus until we reach the ultimate genus. For example, I can refer this book to being, but being is indefinable since I cannot refer it to the superior genus because it is the superior genus. On the other hand, both what is given to us as individual singularity and what represents the ultimate data of sensibility, such as colors, sounds… are indefinable, as well as space and time, since we do not have a genus that includes time and space.

The ultimate foundation of every definition is the indefinable, as if we define man as a rational animal, we would define animal as a living being, living being as being, and we would ultimately reach an indefinable (being). Thus, it is also evident that demonstrations are based on some axioms, which are indemonstrable.2

Genus is the group in which all individuals, in an indefinite and undetermined number, and endowed with certain common characteristics, are ideally gathered. The supreme genus is the one that contains all others.

Species is the term used when two general terms are contained in each other in extension, and the smaller one is called the species, such as in the case of the genus polygon. Man is a species of the animal genus.

We use some terms here that deserve attention. They are: genus, species, specific difference, accident.

Specific difference is the characteristic by which a species distinguishes itself from other species belonging to the same genus. Thus, rational is a specific difference of the species man, which distinguishes it from other animal species.

Accident is what happens, what is neither constant nor essential to the subject of the definition. For example, when we say that “Peter is the person sitting next to the door,” sitting next to the door is just an accident that happens to that person, but it is not essential or constant to them.

Logicians usually provide some practical rules for the proper enunciation of a definition.

The definition must include the nearest genus and the specific difference.

The definition should not be too broad or too restricted. It should be concise and use clear words. While brevity should never make it unintelligible, it should also avoid redundancy of terms or include elements that are foreign to it, that is, expressing more than necessary.

The defining term should not appear in the definition. If the defining term were included in the definition, it would not add anything since it would employ the same term that needs explanation. If someone were to say that “obligation is what obliges us to do or not do something,” they would include in the definition what they seek to define.

Another defect of a definition is being tautological, that is, repeating what should be defined. For example, “matter is extended substance.” And if we were to ask: But what is extended substance? And if the answer were: “it is matter.” Then we would have a vicious circle.3

The definition should not be negative if it can be positive.

We should avoid metaphorical or figurative words in a definition, which instead of clarifying and explaining, can further obscure the notion of what is being defined, as a basic element of the definition should clarify and not complicate or obscure:

These are the main rules of a good definition. With them, one can construct a definition that fulfills its purpose, which is to answer the question: what is this?

Article 2 – Significations

We do not want to conclude this point without giving some information about the theory of meanings that has sparked so much interest among modern logicians.

The theory of meanings emerged from the analysis of thoughts. Thoughts are no longer considered simple, elementary entities, and therefore, they are analyzable, decomposable into their parts. The search for what would be elemental in thoughts, a kind of thought atom, led to meanings. Just as propositions are composed of words, thoughts are composed of meanings.

Certain logicians believe that meanings are simple elements, that is, they are not composed of others. Are they elemental entities? This question is answered as follows: meanings are not elemental entities because, being elements of thought and thought not being an entity, how could they be entities?

Thus, they attribute merely axiological (from axios, value) character to thought.

Values are objects of a different consistency, they say. Values are not entities, but they have value, as the prevailing opinion holds, which we will have the opportunity to analyze and criticize in other works. Thoughts are not entities, that is, ontic things, a term used in modern philosophy that refers to the entity in terms of its form or structure. So, when I say “this house is green,” I can replace this proposition with this: “this house has the value of being green.” In this case, the being green is a meaning of this thought. We have stated that thoughts form a unity. So, how can we admit that meaning is an element? Wouldn’t it be admitting that thought is composed of parts? Yes, say the logicians, thought is a unity, but meanings are not independent units; they form an interdependence with each other.4 Words are not meanings, but merely arbitrary signs, although psychic laws interfere in their formation.

The reader may ask: what is the purpose of this theory of meanings? It was developed to solve the problem of categories. Categories are general meanings that deal with a particular realm, for example, being, unity, reality, ideality, etc. Categories are not determinations of objects but meanings that contribute to the constitution of a thought.

Article 3 – Reasoning

There is a significant difference between thinking and thought; the former is a psychological act that falls under the domain of Psychology, while the latter, apprehended by the former, is properly the object of Logic. The act of thinking, as we have seen, occurs in time, it is variable as a process, whereas thought is timeless and invariant.

Reasoning can be studied from two aspects:

a) the psychological aspect; and

b) the logical aspect, which we will now discuss.

There is a classical definition of reasoning given by Aristotle. Here it is: “Discursive operation by which it is shown that one or several propositions (premises) imply another proposition (conclusion) or, at least, make it plausible.”

In other words, when thinking consists of grasping an ordered series of interconnected thoughts, in such a way that the last thought necessarily follows from the first, we have what is called reasoning. Reasoning only occurs when we infer one thought from another. We can start from a singular fact to reach a general conclusion, or from a general conclusion to conclude that the singular is contained within it. Reasoning can take various forms, but in all of them, there is always the derivation of one thought from another, where the latter contains the former.

We have previously mentioned that knowledge can be acquired through acts of immediate apprehension or through more complex processes, mediate ones (by means of…). In the first case, we have intuitive knowledge, and in the second case, discursive knowledge.

The former is obtained through direct experience, for example, when I verify that this table is larger than the book. Discursive knowledge, or rational knowledge, results from previous knowledge, and we can give the example: “every man is mortal.”

We only arrive at this knowledge after verifying a series of facts and reaching a subsequent conclusion.

Discursive processes can be simple or complex:

a) simple when one knowledge is directly inferred from another; it is also called immediate inference;

b) complex when the transition from one knowledge to another is made through at least one intermediate member, such as deductive reasoning, mathematical reasoning, inductive reasoning, and reasoning by analogy.

In complex discursive processes (mediate reasoning, as we have seen), the transition from one knowledge to another is made through at least one intermediate member.

Traditionally, there are two known types: induction and deduction. Induction is generally defined as the transition from the particular to the general, while deduction is the transition from the general to the particular.

In reasoning, there are apprehensions of thoughts and their meanings, and these form a whole, a unity. This occurs in intuitive reasoning.

In discursive reasoning, one thought is inferred from another. Thus, discursive reasoning reduces to intuitive reasoning, as it is merely a complex form of the latter.

Deduction is based on logical principles (principles of identity, non-contradiction, excluded middle, and sufficient reason, which we have already discussed), which are true axioms for Formal Logic, governing all logical entities and ideal objects.

Induction is not based on logical principles but on the assumption of regularity in the course of nature, on a certain homogeneity in the succession of facts, a hypothetical regularity for many, but which is fundamental for induction, upon which it is based. The so-called scientific laws, the inductions of science, are based on the repetition of singular facts and the regularity of their repetition. Thus, for example, the regularity of planetary movements is not grasped by reason but by the repetition of facts. If the facts of physical reality are examined, it is easy to see that they have something to do with reason. However, the observation of singular and particular facts has allowed us, based on the postulate of the regularity of cosmic facts, the foundation of science, to establish the hypothesis that they will continue to occur in the future, which leads to the formulation of induced universals.

There is no sensible intuition of the universal. Sensible intuition is only of the singular, the individual, as we have seen many times before. The universal is founded on singular facts. Therefore, deduction is based on prior induction. However, the formulation of a universal implies accepting the possibility of formulating the universal. Hence, we have to admit that, to formulate a universal from an induction, the acceptance of the possibility of the universal is a prerequisite. How is this possibility given to us? It arises from the repetition of facts, whose occurrence, in the past and present, leads us to believe in their reproduction in the future. As the future confirms the actualization of this possibility, under the influence of the rational part of our mind, which desires homogeneity (based on similarity), we postulate that there is regularity in cosmic facts. Based on this regularity, we can make the leap from induction to the universal, which is the starting point for subsequent deduction. Therefore, the attainment of the universal is not merely a consequence of induction, as it is corroborated by accepting the principle, whether hypothetical or not (which is not currently up for discussion), of a universal regularity, a certain universal legality, that the cosmos is indeed ordered by constants that do not vary (invariants) and allow for the formulation of universal principles.

Theme IV

Article 1 – Syllogism

Of the discursive processes we have discussed, we highlight deductive reasoning among them, which has been identified with the syllogism.

The syllogism is a formal deduction; it is a form of reasoning that goes from the general to the particular or singular. It consists of establishing the necessity of a judgment (conclusion), showing that it is the forced consequence of a judgment recognized as true (major) through a third judgment (minor), which establishes a necessary connection between the first two.

Thus, we have two premises – the name given to the first two judgments – from which a third, called the conclusion, is inferred.

Let’s give a classic example of a syllogism:

All men are mortal (Major Premise) Now, Socrates is a man (Minor Premise) Socrates is mortal (Conclusion).

Being a deductive reasoning, the starting point is always a universal judgment, whether it occupies the first position, the place of the major premise, or not.

The syllogism has three terms: the major term, the middle term, and the minor term. These terms are the ones that appear in the judgments (or propositions) that constitute the syllogism.

The predicate of the conclusion is called the major term.

Let’s examine the aforementioned syllogism: Mortal is the major term.

The subject of the conclusion is called the minor term. The subject of the conclusion is Socrates. The middle term is the one present in both premises but absent from the conclusion, which is man in this example.

If instead of considering the three judgments that constitute the syllogism, we consider the three terms that appear in these judgments, the syllogism consists of establishing that one of these terms, the major term, is the necessary attribute of the other, the minor term (that mortal is the attribute of Socrates), because it is the necessary attribute of a third term, the middle term (man in our case, man is mortal), which in turn is the necessary attribute of the minor term (Socrates, as man is an attribute of Socrates). In summary, mortal is the necessary attribute of Socrates because it is the necessary attribute of man, and every man has the attribute of being mortal.

Thus, the syllogism consists of showing that an object or a class of objects belongs to another class because it or he belongs to a class of objects that, in turn, belongs to that other class.

This syllogism can be reduced to a simple formula: let’s call the major term C, the middle term B, and the minor term A, which in our example would be:

B is contained in C, and A is contained in B, therefore A is contained in C.

Syllogism rules: There are eight rules that the scholastics formulated through Latin verses:

Terminus esto triplex, medius, majorque minorque (The syllogism has three terms: the major, the middle, and the minor). This is necessary to make the comparison of the two with a third.

Nequaquem medium capiat fas est (The conclusion must never contain the middle term).

Aut semel aut medius generaliter esto (The middle term must be taken at least once in its entirety). Yes, because the middle term serves to compare the extremes, and in the conclusion, the result, that is, the relationship between the extremes, must appear.

Latius hunc (terminum) quam premissas concluso non vult (No term can be more extensive in the conclusions than in the premises). This rule is a consequence of the first rule, as if they were more extensive, the terms would be altered.

Utraque si praemissa negat nil inde sequitur (If both premises are negative, nothing can be concluded). It is clear that nothing can be concluded from two negative judgments. If two terms do not identify with each other, how can they both identify with a third term? And if two terms do not identify with a third term, it does not mean they are identical to each other. If house is not animal and if hat is not animal, house is not necessarily hat. Two terms equal to a third term are equal to each other. Two terms not equal to a third term are not necessarily equal to each other.

Ambae affirmantes nequeunt generare negantem (Two affirmative premises cannot produce a negative conclusion). Yes, because if two terms identify with a third term, they are necessarily identical to each other and cannot be distinct from each other.

Pejorem sequitur semper conclusio partem (The conclusion always follows the weaker part). The particular or negative premise is called the weaker one. This rule is derived from rule number 4. The terms cannot have greater extension in the conclusion than in the premises, as we said. Now, if one of the premises is particular or negative, the conclusion must be particular or negative. It is clear that if one extreme is equal to a third term, and the other is not, we can never conclude that one is the other. Therefore, the conclusion cannot be affirmative if one premise is negative.

Some A are B

Some B are C.

We cannot know if the some B in the second premise precisely refers to the B in the first premise, which would result in four terms instead of three, violating the first rule. Moreover, the middle term is not taken in its entirety in any of the premises, which violates rule number 3. If both premises are negative, there is no conclusion according to rule number 5.

Modes and Figures of Syllogisms – In Logic, the figures of the syllogism are called the forms it adopts based on the position of the middle term in the major or minor premises. The four possible forms are called the four figures, which are characterized as follows:

By having the subject term in the major premise and the predicate term in the minor premise. Ex.: All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal;

By having the middle term as the predicate in both premises: "All men are rational; no plant is rational; therefore, no plant is a man;

By having the middle term as the subject in both premises: “Some men are philosophers; all men are bodies; therefore, some bodies are philosophers”;

By having the middle term as the predicate in the major premise and the subject in the minor premise: “All men are mortal; all mortals are animals; therefore, some animals are men”.

The mode of the syllogism results from the quantity and quality of the premises that compose it. These judgments fall into four classes, as we have already studied:

Universal affirmative (A), Universal negative (E), Particular affirmative (I), Particular negative (O).

They can be combined in 64 forms, but not all of them are conclusive. If we apply the studied rules, we have 19 valid modes, which are distributed as follows:

4 for the first figure; 4 for the second; 6 for the third, and 5 for the fourth.

Since each judgment is symbolized according to its quantity and quality by a vowel, each valid mode is traditionally symbolized in logic by a Latin word that contains the sign-letters of the judgments that compose the syllogism.

These are the valid modes for each figure:

First figure

A A A (Barbara)

E A E (Celarent)

A I I (Darii)

Second figure

E I O (Ferio) E A E (Cesare)

A E E (Camestres) E I O (Festino) A O O (Baroco)

Third figure

A A I (Darapti) E

A O (Felapton) I A

I (Disamis) A I I (Datisi)

O A O (Bocarão)

E I O (Ferison)

Fourth figure

A A I (Bamalip) A

E E (Camenes)

I A I (Dimatis)

E A O (Fesapo)

E I O (Fresison)

Examples: from the first figure: The middle term is the subject in the major premise and the predicate in the minor premise.

Barbara:

A. All metal is a body;

A. all lead is metal;

A. therefore, all lead is a body.

Celarent:

E. No metal is a plant; A. all lead is metal;

E. therefore, no lead is a plant.

Darii:

A. All metal is a body; I. some mineral is metal;

I. therefore, some mineral is a body.

Ferio:

E. No metal is a living being; I. some body is metal; O. therefore, some body is not a living being.

Examples from the second figure: The middle term is the predicate in both premises.

Cesare:

E. No living being is metal; A. all lead is metal;

E. therefore, no lead is a living being.

Camestres:

A. All lead is metal; E. no plant is metal;

O. therefore, no lead is a plant.

Festino:

E. No plant is metal; I. some body is metal; O. therefore, some body is not a plant.

Baroco:

A. All lead is metal;

O. Some body is not metal;

O. therefore, some body is not lead.

Examples from the third figure: The middle term is the subject in both premises.

Darapti:

A. All metal is mineral; A.

all metal is a body; I. therefore,

some body is mineral.

Felapton:

E. No metal is a plant; A. all metal is a body;

O. therefore, some body is not a plant.

Disamis:

I. Some metal is lead; A. all metal is a body; I. therefore, some body is lead.

Datisi:

A. All metal is a body; I. Some metal is lead;

I. therefore, some body is lead.

Bocardo:

O. Some metal is not lead; A. all metal is mineral;

O. therefore, some mineral is not lead.

Ferison:

E. No metal is a plant; I. some metal is lead; O. therefore, some lead is not a plant.

Examples from the fourth figure: The middle term is the predicate in the major premise and the subject in the minor premise.

Bamalip:

A. All metal is a body;

A. all bodies occupy space;

I. therefore, some bodies that occupy space are metal.

Camenes:

A. All Brazilians are Americans;

E. no American is European;

E. therefore, no European is Brazilian.

Dimatis:

I. Some Americans are from São Paulo;

A. all Paulistas are Brazilians;

I. therefore, some Americans are Brazilians.

Fesapo:

E. No Paulista is French;

A. All French people are Europeans;

O. therefore, some Europeans are not Paulistas.

Fresison:

E. No Brazilian is European;

I. some Europeans live in Brazil;

O. therefore, some men who live in Brazil are not Brazilians.

All these modes and figures that we present here are done exclusively to comply with the old norms of formal logic. However, all these rules and norms can be reduced to just one law of syllogism, based on an ontological principle: Two things equal to a third thing are equal to each other. If these two things are not equal to a third thing, but only in part, they may not be equal to each other, not even in part.

If A is partially equal to B, and C is equal to B, it does not mean that A is equal to C, not even in part.

Everything that can be affirmed or denied about the entirety of a genus can also be affirmed or denied about all the individuals that compose that genus. This is a principle of syllogism that follows from the principle of identity.

“All men are mortal, therefore a man (Socrates) is mortal.” All figures of syllogism (2nd, 3rd, and 4th) can be reduced to the first figure, which Aristotle called a perfect syllogism and which is the concrete application of the rule we mentioned above. Thus, it can be seen that the syllogism is just a form of deductive reasoning, as we have already explained.

In everyday language and even in more precise demonstrations, one of the articulations of the syllogism is implied when it is evident. The syllogism is then called an enthymeme. In an enthymeme, one of the premises is omitted. For example: all metal is heavy because all matter is heavy. The premise “all metal is matter” is omitted.