Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, in a letter written in 1691, discusses whether the essence of body consists solely in extension, as many people believed at the time. He argues that if this were the case, then extension alone would explain all the properties of matter, which is not the case. He believes that there is more to matter than just extension, including the quality of natural inertia. He argues that the notion of substance, action, and force must be added to extension to fully understand the nature of matter. Leibniz believes that this consideration is important not only for understanding the nature of matter but also for recognizing the higher and immaterial principles in physics.

(Journal des Savants, June 18, 1691, page 259)

You ask me, sir, for the reasons why I believe that the idea of body or matter is other than that of extension. It is true, as you say, that many able people today are prejudiced towards this belief, that the essence of body consists in length, width, and depth. However, there are still some, who cannot be accused of being too attached to scholasticism, who are not satisfied.

Mr. Nicole, in one part of his Essays, testifies to being one of this number, and it seems to him that there is more prejudice than light in those who do not appear to be frightened by the difficulties that are encountered.

It would take a very extensive discourse to explain what I think about this matter distinctly. However, here are some considerations that I submit to your judgment, of which I beg you to inform me.

If the essence of body consisted in extension, that extension alone should suffice to account for all the affections of body. But this is not the case. We observe in matter a quality that some have called natural inertia, by which body in some way resists movement; so that some force must be employed to set it in motion (even abstracting from gravity) and a large body is more difficult to move than a small body. For example:

|

| Fig. 1. |

If the moving body A encounters the resting body B, it is clear that if the body B were indifferent to movement or rest, it would be pushed by body A without resistance, and without decreasing the speed or changing the direction of body A; and after the collision, A would continue on its path, and B would go with it, keeping pace. But it is not so in nature. The larger body B is, the more it will decrease the speed with which body A comes, even making it reflect whether B is larger than A. Now, if there were only extension or situation in bodies, that is, what geometers know about them, combined with the notion of change alone, that extension would be entirely indifferent to this change; and the results of the collision of bodies would be explained by the mere geometric composition of movements; that is, after the collision, the body would always move with a movement composed of the impression it had before the impact, and that it would receive from the colliding body, to not impede it, that is, in this case of collision, it would move with the difference of the two speeds, and in the direction of the collision.

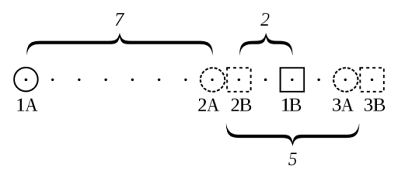

|

| Fig. 2. |

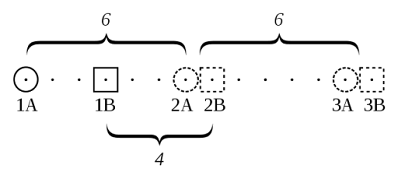

|

| Fig. 3. |

As the velocity 2A, 3A, or 2B, 3B, in figure 2, is the difference between 1A 2A and 1B 2B; and in the case of collision, figure 3, the faster would overtake a slower one that is ahead of it, the slower one would receive the speed of the other, and generally they would always move together after the collision; and in particular, as I said at the beginning, the one that is in motion would carry with it the one that is at rest, without receiving any decrease in its speed, and without the size, equality, or inequality of the two bodies changing anything in all this; which is entirely irreconcilable with experiments. And even if one were to suppose that size should make a change in the movement, there would be no principle for determining the means of estimating it in detail, and knowing the resulting direction and speed. In any case, one would lean towards the opinion of the conservation of movement; whereas I believe I have demonstrated that the same force is conserved,1 and that its quantity is different from the quantity of movement.

All this makes it clear that there is something in matter other than what is purely geometrical, that is to say, extension and its change, and its naked change. And upon considering it well, one realizes that one must add some higher or metaphysical notion to it, namely that of substance, action and force; and these notions imply that everything that suffers must act reciprocally, and that everything that acts must suffer some reaction; and therefore that a body at rest should not be carried away by another in motion without changing something in the direction and speed of the agent.

I agree that naturally every body is extended, and that there is no extension without a body. However, one should not confuse the notions of place, space, or pure extension with the notion of substance, which, in addition to extension, also includes resistance, that is to say, action and passion.

This consideration seems to me important not only for understanding the nature of extended substance, but also for not disregarding the higher and immaterial principles in physics, to the detriment of piety. For although I am convinced that everything is done mechanically in the bodily nature, I also believe that the very principles of mechanics, that is to say, the first laws of motion, have a more sublime origin than pure mathematics can provide. And I imagine that if this were better known or better considered, many people of piety would not have such a poor opinion of corpuscular philosophy, and modern philosophers would better unite the knowledge of nature with that of its author.

I will not dwell on other reasons concerning the nature of body; for that would lead me too far.

-

Journal des Savants, year 1686.↩

No comments:

Post a Comment